Economic Corridor Development in Cambodia:

A Cambodian Perspective on Economic Corridors Development

Dr. Bob Nanthakorn

National University of Management, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

1. Introduction

In the 1990s, after struggling under the 1970s Khmer Rouge dictatorship and subsequent civil war and socialist-oriented economy in the 1980s, Cambodia’s political and economic stability began to increase. Sovereignty was regained and social order reinstated. International links were established or reactivated. (Hatsukano et al., 2012; Kuroiwa & Tsubota, 2013; Sisovanna, 2012a)

Despite having one of the weakest economies in Southeast Asia, Cambodia has recently had among the highest annual growth rates in gross domestic product (GDP) worldwide. During the past two decades, it economic growth rate averaged 7.6%, mainly from tourism, exporting manufactured goods, and real estate. (World Bank, 2024) The current national GDP is 28.82 billion United States dollars (bn USD; O’Neill, 2023) 38% of which was generated by industry, 35% by services, and 21% by agriculture. The most recent World Bank (2024) data forecasts 5.8% economic growth for 2024. In 2023, the inflation rate was 1.9%. In recent decades, foreign direct investment (FDI) has grown considerably. In 2022, FDI was at 1.1bn USD, with 80% from China. Other major investments were from South Korea, Hong Kong, and Viet Nam. (GIZ, 2023)

Cambodia’s imports of 29.79bn USD exceeded exports of 22.47bn USD. (O’Neill, 2023) The most significant imports in 2023 were from China (46%), Viet Nam (16%), and Thailand (12%), whereas exports primarily went to the United States of America (USA) (36%), Viet Nam (11%), and China (5%). (GDCE, 2024 a & b)

After decades of political, cultural, and economic isolation, initiatives were taken to reconnect Cambodia to regional and international markets. In particular improvements were made to boost import and export of goods, facilitate business, build foreign investment, and improve national infrastructure. An avenue for such developments was to define, initiate, and join national and international frameworks and economic corridors. (Sophorndara, 2009) In the following sections, economic corridors relevant to the contemporary Cambodian economy are described:

2. Economic Corridor Development in Cambodia

2.1. National Economic Corridor Development

2.1.1. Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in Cambodia

In 2005, Cambodia introduced special economic zones (SEZs) managed by the Cambodian Special Economic Zone Board (CSEZB). These zones aim to attract potential investors by providing an attractive logistical infrastructure, straightforward administrative processes, and simplified import and export procedures. SEZs are defined regions with more liberal economic laws to offer additional incentives to investors. (Ishida, 2009; Sisovanna, 2011; Tam, 2019) Sub-decree No.148 was issued by the Cambodian Royal Government to establish and manage SEZs by defining their purpose to simplify and facilitate investment conditions and appeal to boost national economic growth, productivity, competitiveness, trade, and job creation while reducing poverty. (CDC, 2005)

The key terms and conditions to establish a SEZ are summarized (CDC, 2005; Sisovanna, 2011):

- 50 acres or more of land with exact coordinates and geographic boundaries bordered by a fence.

- Offices for the zone administration and its management, sufficient roads and adequate networks for electricity, fresh water, and telecommunications.

- Environmentally relevant installations, such as a wastewater treatment network and places to store and manage waste.

- Safety measurements, especially fire protection and security systems.

In addition, the sub-decree mentions the possibility of installing infrastructure for use by workers, comprising schools, parks, restaurants, and shopping outlets. SEZ workers may also receive better salaries and career opportunities. (CDC, 2005; CSHK, 2021)

Main incentives for investors in a SEZ as specified in the sub-decree include up to nine years of tax exemptions, additional exemptions on import taxes and other duties for the import of construction materials and equipment, and a 0% rate for value added taxes if all requirements are met. (CDC, 2024; Sisovanna, 2011)

The Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC) tries to cluster certain industries and is approaching certain focus industries for specific SEZs. The focusses of different SEZs seems comparatively broad and levels of specialization and clustering low: (CDC, 2024 b & c & d)

- Poi Pet PP SEZ: car parts, electronics and textiles, plastic parts, wiring.

- Koh Kong SEZ: car assembly, car wiring systems, sport textiles and accessories, electronics.

- Phnom Penh SEZ: car parts, electronics, textiles, food.

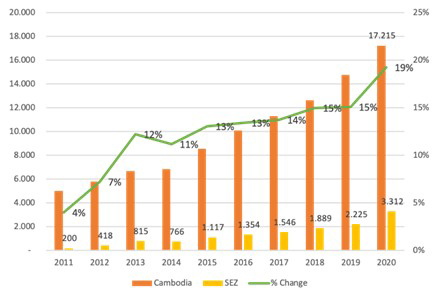

Today, the CDC identifies 24 operational SEZs covering over 560 investment projects and employing over 160,000 workers. (CDC, 2024a) The number of SEZs and exports generated in these zones are displayed in

Figure 1 Cambodian exports (in bn USD) from 2011 to 2020 and export share originating from SEZs

(Source: CDC, 2024a)

Since the establishment of the SEZs in the mid-2000s, the total exports generated in these regions has increased significantly, as seen in Figure 01. Reports concluded that SEZs are catalysts for regional development. Today, most SEZs are located near the capital city of Phnom Penh; in a southern Cambodian belt from the coastline to the Vietnamese border (Sihanoukville, Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Cham, Svay Rieng); or in the north along the border to Thailand (Banteay Meanchey). (CDC, 2024a; Ishida, 2009; Seng et al., 2021) Considerable potential is seen in linking SEZs in Cambodia to similarly functioning economic zones in Thailand, for example to the Eastern Seaboard / Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). (Tangtipongkul et al., 2021) An exploration of the development of SEZs in Cambodia by Tam (2019) revealed that these zones are particularly successful if links between businesses inside the SEZ are more closely connected to relevant supply chains and if they are efficiently linked across international borders. However, Tam’s analysis did not provide clear evidence to link SEZ growth to increased foreign direct investment (FDI). A map of the major SEZ locations is seen in Figure 02:

Figure 2 Map of major Cambodian SEZ locations

(Source: Seng et al., 2021)

2.2. Bilateral Economic Corridor

2.2.1. Bilateral Agreement on Navigation between Cambodia and Viet Nam

In 2009, the Cambodian and Vietnamese governments signed a mutual agreement on using common waterways for transportation. The main objective of this agreement was to implement regulations facilitating the use of the Mekong River as a transportation route for transit and cross-border trading activities. (Suthy, 2022; Vietnamese & Cambodian Government, 2009) The treaty raised hopes that river-based customs functions and immigration procedures could be performed to increase efficiency. (Dezan Shira & Associates, 2009) In 2022 joint statements, both countries reasserted their commitment to ensuring efficient and sustainable use and preservation of Mekong water resources. (Vietnamese & Cambodian Government, 2022) Although this agreement does not mention the term ‘economic corridor’, its characteristics of facilitating trade along the multinational Mekong River has comparable effects and potential positive benefits.

2.2.2. Bilateral Agreements on Road Transportation between Cambodia and Viet Nam or Laos

In addition to the above described agreement on navigation, Cambodia has signed four agreements over the past three decades with its neighbor Viet Nam as well as with Laos on road transportation, regulating and facilitating cross-border transport of goods and passengers. (Kingdom of Cambodia, 1999 & 2007, 2009, 2013)

2.3. Regional Economic Corridors Development

2.3.1. A look back: The Road Project

In the early 1990s, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) funded an initiative to encourage economic cooperation in the subregion. The project’s objective was to facilitate collaboration between Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and China’s Yunnan Province for development of six key sectors: transportation, telecommunication, energy, human resources, the environment, and improvements in trade and investment. The strongest emphasis was placed on bettering transportation links, leading the initiative to become known by the unofficial name ‘The Road Project’. Uniquely, this project was the first time such development activities were planned, organized, and performed on a country-specific basis focused on subregional development. Several major road projects began, leading to improved cross-border sections. In 1993, the initiative was titled Economic Cooperation in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), which is described in the following subchapter. (Ishida & Isono, 2012)

2.3.2. The Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)

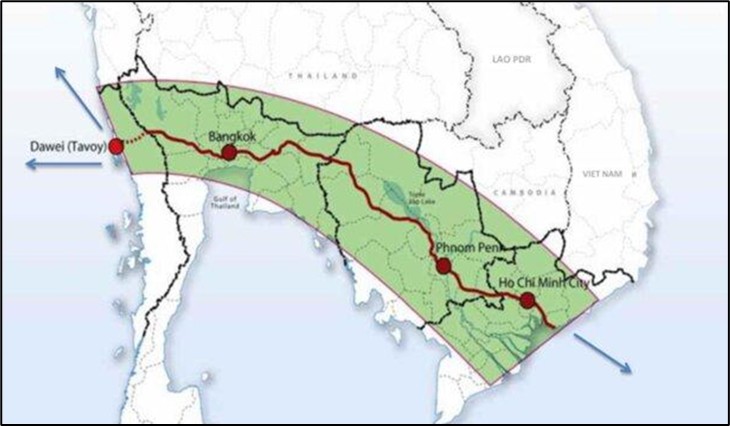

The regional focus of GMS efforts are divided into three major corridors: the East–West Economic Corridor (EWEC) from Viet Nam to Laos and Thailand to Myanmar; the North–South Economic Corridor (NSEC) linking China, Laos, Myanmar, and Thailand; and the Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) connecting Cambodia with its direct neighbor to the west, Thailand, and its direct neighbor to the east, Viet Nam, and proceeding to Myanmar. A map of the major GMS corridors is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

(Krongkaew, 2004)

The Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)

The SEC is the main GMS corridor with a major direct impact on Cambodia. The expected benefits of establishing the SEC included heightening regional investment attractiveness by improving infrastructure and local regulations. The SEC aimed to encourage and extend trading with Cambodia’s direct neighbors Thailand and Viet Nam and reduce the Cambodian trade deficit. (Brunner, 2013; Ksoll & Brimble, 2012; Mekong Institute, 2017, Phyrum et al., 2007) Although many countries anticipated strategic opportunities from participating in GMS trading routes, the SEC baseline was characterized by many obstacles, including insufficient infrastructure, unskilled workers, low population density, poverty, illiteracy, and lack of support from local authorities. (Guina, 2008; Phyrum et al., 2007) A map of the SEC with two subcorridors is shown in Figure 04.

Figure 4 Map of the Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) and two of its three Subcorridors

(Source: Mekong Institute, 2017)

The SEC traverses eight Thai provinces, four zones and 21 provinces in Cambodia, and four regions in Viet Nam. Over 12 million people, representing over 90% of the Cambodian population, live in or along SEC routes. It is divided into three subcorridors:

- A Northern subcorridor from Bangkok through Siem Reap to Quy Nhon.

- A Central Subcorridor covering populous agricultural zones close to the Tonle Sap Lake and connecting three regional commercial centers: Bangkok, Phnom Penh, and Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon).

- A Southern Coastal Subcorridor covering industrial and touristic zones along the Cambodian coastline, linking to major neighbouring industrial zones: the eastern seaboard or EEC in Thailand and major industrial zones in southern Viet Nam. Opportunities for economic growth are seen especially in the sectors of fisheries, food industry, tourism, energy, trading and light industry (consumer goods, agricultural products, and food) mainly located in Sihanoukville. The link to the EEC is seen as possessing especially great potential for the SEC. (Tangtipongkul et al., 2021; Phi, 2012)

In addition to these three subcorridors, there is an inter-corridor allowing connections between the subcorridors and the EWEC. (Phyrum et al., 2007; Sisovanna, 2012a; Tangtipongkul et al., 2021)

In the GMS founding year of 1993, five principles were defined for selecting and prioritizing projects (Ishida & Isono, 2012):

Prioritizing improving extant facilities rather than building new ones.

- Primary focus on extant agreements among partner countries, with not all six countries required to be involved in every agreement

- Accentuating trade-generation potential

- Transportation projects should be executed sectionally for facilitation and rapid benefits

- Criteria for project selection should be established for financial aspects

Projects selected based on these principles should meet the following objectives: (Sotharith, 2007)

- Lead to improvements in subregional infrastructure, especially transportation and communication links

- Improve bases for subregional trade and investment

- Upgrade subregional cooperation on energy projects

- Decrease trans-border issues, such as standards, certifications, and accreditations

- Support human resources by education and training

- Respect environmental interests

The East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)

The second GMS corridor impacting Cambodia is the East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC), although less influential than the SEC, with a main route not traversing Cambodia itself. (see map in figure NN) It extends from central Myanmar through all of northern Thailand, southern Laos, and concludes in central Viet Nam. This main route links to northern Cambodia, providing potential regional benefits from the EWEC. (Phon-ngam, 2021)

2.3.3. Cambodia-Laos-Viet Nam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA)

In 1999, the prime ministers of Cambodia, Laos, and Viet Nam (the CLV) established an agreement for common development: the Cambodia-Laos-Viet Nam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA). Its key goal was to boost prosperity in all three countries, especially by promoting economic growth, reducing poverty and disparities, and securing sustainability. This would be done by extending and upgrading extant transportation systems, especially roads, seen as essential for attaining major socioeconomic improvements. In 2004, a development master plan was finalized for socioeconomic improvements. Japan pledged financial support for the development projects (Sisovanna, 2012a). Trinational cooperation raised hopes for increased FDI leading to economic growth and reduced poverty in the triangle. Simultaneously, infrastructure-related challenges (roads, energy, communication); logistics (storage and warehousing); and human resources (skills, training, social aspects) required mastering to obtain improvements. (Sisovanna, 2012b) During a 2023 meeting of the CLV Joint-Coordinating Committee meeting with the theme “Strengthening the CLV Parliament Roles in Advancing Cooperation, Partnership, Solidarity, and Prosperity,” all parties reiterated a willingness to further increase mutual activities for regional development and follow the master plan. (CPP, 2023)

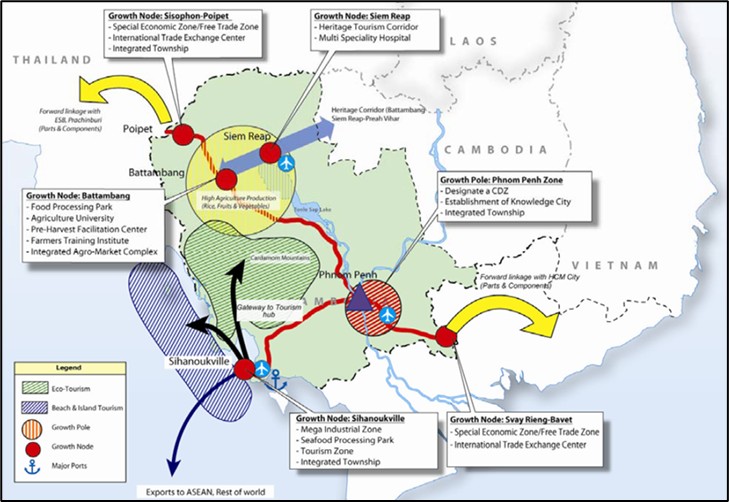

2.3.4. Mekong-India Economic Corridor (MIEC)

The Mekong-India Economic Corridor (MIEC) covers regions in Viet Nam, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and India. It spreads in a broad belt from northern and central Viet Nam by central Cambodia and Phnom Penh to central Thailand and Bangkok, passing through Myanmar before connecting to India.

The key motivation for the MIEC is to more decisively link international manufacturing sites and trading centers, especially connecting them to India. (Ambashi et al., 2020; ERIA, 2009; Isono, 2010) The MIEC resembles the SEC, but does not pertain to subcorridors; it also includes additional routes to Myanmar and India, building potential for positively contributing to the GMS. (Ishida & Isono, 2012) A visualization of the MIEC and its proposed initiatives is seen in Figures 5 and 6.

2.3.5. Ayeyawady – Chao Phraya – Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS)

The Ayeyawady – Chao Phraya – Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) is an initiative of Thailand, Laos, Viet Nam, and Cambodia that aims to decrease the economic gaps between these nations, especially by facilitating trade and investment. It intends to use established regional programs and sees its activities as complementary to existing cooperative initiatives, for example the GMS. Several projects have been initiated involving two or more countries with a focus on transportation projects in the SEC and NWEC. (Mephokee et al., 2014; Supatn, 2012)

Figure 5 Map of the Mekong-India Economic Corridor (MIEC)

(Source: Ambashi et al., 2020, originally in: ERIA, 2015)

Figure 6 Proposed MIEC Initiatives related to Cambodia

(Source: ERIA, 2009)

2.4. International Economic Corridors Development

Economic corridors in Cambodia have been described in the first section of this chapter. Economic corridors beyond the borders of Cambodia have been described in the previous two sections divided by bilateral and regional (multinational) economic corridor development. There is currently no further international economic corridor development with Cambodian participation, apart from these economic corridors.

3. Challenges to Economic Corridor Development in Cambodia

As described in the previous sections, economic corridors have led to major economic, social, and structural improvements in Cambodia. In addition to the described benefits, there have also been challenges related to developing economic corridors, as described in subsequent sections.

3.1. Infrastructure challenges

- A weak, inefficient, and antiquated transportation infrastructure was identified as a major obstacle during the SEC creation. (Chheang & Wong, 2014; Phyrum et al., 2007; Sisovanna, 2012a) Since the foundation phase, several roads have been, or are being, upgraded. (Sisovanna, 2012a) Apart from road transportation, there are two railway lines in Cambodia located in SEC subcorridors: a northern line 386 kilometers (km) long, starting in Phnom Penh and leading to Banteay Meanchey Province lies in the Central Subcorridor, and a southern line 264 km long also starts in the capital and ends in Sihanoukville in the Southern Coastal Subcorridor. Passengers, oil and construction materials are transported. (Sisovanna, 2012a) In addition, Cambodia contains about 1,750 km of navigable inland waterways, of which only 580 km may be used year-round. Main waterways include the Mekong River, Tonle Sap Lake, Tonle Sap River, and Bassac River. The major river port is Phnom Penh, which after an upgrade can handle large shipping containers. (Sisovanna, 2012a) Thangavelu et al. (2023) describe a positive correlation between highway and road quality and the decision to allocate FDIs. Malar (2014) states that 90% of GMS development activities have focused on transportation. However, only NSEC and EWEC corridor activities have been developed effectively, unlike the SEC. (Malar, 2014) Isono (2019) analyzes the economic impact of the latest development in subcorridors, summarizing three key findings: 1) improved roads have positive local impact more than nationwide; 2) main positive effects were in the service sector; 3) The research states that improved roads are especially beneficial economically if linked to industrial real estate development. The latest Comprehensive Asia Development Plan (CADP 3.0) of 2022 reports SEC improvements in terms of infrastructure, trade, investments, and tourism. It highlights enhanced road infrastructure projects such as the National Road No. 1 and No. 5 and the new Tsubasa Bridge. Over the past decades, the Economic Research Institute for Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and East Asia (ERIA) has issued three Comprehensive Asia Development Plans (CADP). The latest, CADP 3.0, identifies as a major challenge for the SEC the delayed completion of the Stung Bot Cross Bridge, an essential Cambodia-Thailand border crossing. (ERIA, 2015 & 2022)

- In addition, insufficient electricity networks have been scrutinized in the past. In 2000, fewer than 10% of Cambodians had access to steady electricity. Since then, access has quickly increased to over 97%, reducing negative effects from this issue. The Cambodian government initiated several initiatives to improve and extend the national electricity network. (GIZ, 2023) Problems remain, especially in rural areas, where the electricity access rate of 82% is significantly lower than in urban areas. (Akbas et al., 2022) In 2023, nearly half of all Cambodian enterprises experienced electrical outages, essentially similar to results across East Asia and the Pacific and inferior to overall results for lower-middle income countries. (World Bank, 2023)

- Despite major past issues, Cambodia has heightened digital transformation. Today, the mobile phone usage rate is above 100% (as some individuals possess more than one mobile phone) and the country contains more than seven million broadband connections. Nevertheless, issues remain related to digital usage and literacy skills, and high-speed internet availability in rural areas (coverage urban: 100%; rural: 70%) remains disproportionate. (te Velde et al., 2020)

- Ishida (2007), who explored GMS effectiveness at an early point, concluded that Central Subcorridor projects were effective, but Northern Subcorridor ones were not. Evaluating economic cooperation in the GMS subregion, Duval (2008) concluded that all GMS countries saw major improvements in socioeconomic development. The research also highlights difficulties in the size of the regional nations and economies, describing Laos and Cambodia as small countries with modest economies, in which the development gap has not decreased as significantly as in other regions.

- The development level in Cambodia differs from that in larger, stronger developed neighbors, Thailand to the west and Viet Nam to the east. Khmer Rouge rule left much-diminished structural, social, educational, and economic aspects, compared to Cambodia’s neighbors. (Chheang & Wong, 2014; DAN, 2005) Krongkaew (2004) analyzed the GMS, identifying challenges specifically arising from variations in local development grades between member countries. Political instability in some countries has also been identified as a source of inefficiency in the development process. Although Cambodia has made noteworthy progress, the gap remains, leaving it behind other ASEAN nations. (Chheang & Wong, 2014; DAN, 2005)

- The educational and training level among Cambodian people is low, hindering full human resource capacity. Lack of abilities to perform tasks requiring advanced technology and management skills was described as a major concern. (Chheang & Wong, 2014; Phyrum et al., 2007; Sisovanna, 2012a; Thangavelu et al., 2023) Chheang and Wong (2014) argue that a lack of human resources, especially skilled labor, inadequate infrastructure, and institutional flaws, are principal obstacles to economic reform and transformation. Simultaneously, the English proficiency level of Cambodian workers, especially younger staff, is seen positively by investors. Engineering and other courses are becoming more complex, but to satisfy market demands, more university programs are required. (GIZ, 2023)

- Poverty, inequality, high HIV infection rates, and human trafficking are major social issues hindering socioeconomic growth. There are high variations in income and living standards across different regions of Cambodia. (Phyrum et al., 2007; Sisovanna, 2012a)

- Many different ethnicities inhabit the DTA, with over 30 different ethnic groups in the relevant regions in Cambodia, 40 in Viet Nam, and 15 in Laos. (Sisovanna, 2012a)

3.2. Institutional challenges

- Differences between Cambodia and its neighbors in understanding market economy concepts are leading to issues in integrating regional economic systems. In recent decades, Cambodia has been following a liberal market economy, but its neighbors Viet Nam and Laos remain socialist-oriented. (Chheang & Wong, 2014)

- An obstacles in the SEC was a lack of awareness and support for economic corridors by local authorities (Phyrum et al., 2007). Thangavelu et al. (2023) see a need to create a higher level of transparency on taxation and other regulations.

- In addition to a lack of awareness from local authorities, awareness by local residents has also been described as low. (Phyrum et al., 2007)

- Actions planned and executed in the corridors are designed to improve the lives of the local population. However, displacements of individuals, families, and complete communities are sometimes required to proceed with investment programs. (Phyrum et al., 2007; Sisovanna, 2012a)

- Investment incentives are often limited with respect to time, for example in the SEZs. There is a risk that investments and businesses will erode over time, when attractiveness of investments decreases after incentives expire. Alternate investment opportunities beyond Cambodia might appear more attractive. (Sisovanna, 2011)

- Also, SEZs bordering Cambodia and Thailand, for example SEZ Trat, do not always efficiently promote joint business opportunities, such as in the fishing, agricultural, and food industries or in tourism. (Tangtipongkul et al., 2021) Exploring cross-border trade barriers between Cambodia and Thailand, Ratanasithi and Jaroenwanit (2012) assert that neither state facilitated trade flows sufficiently. They list thirteen barriers, of which seven are Cambodia-related. Among these are unclear regulations, difficult import procedures, currency instability, high transportation costs, poor road conditions, and difficulties in Cambodia-Thailand relations. A World Bank survey (2023) declared that export clearance took an average of eight days, which is comparable to lower middle income countries worldwide or the average in East Asia and the Pacific. Import clearance took an average of nine days, similar to the regional average, but significantly shorter than lower middle income countries generally.

- Tam (2019) and Thangavelu et al. (2023) concluded that SEZs have no clear positive or negative impact on FDI. Most FDI between 2017 and 2020 was made outside of SEZs. Thangavelu et al. (2023) adds that investment in SEZ logistics and infrastructure might be insufficient and lack the desired trade support facilitation.

3.3. Logistics service provider challenges

- Ishida & Isono (2012) described major challenges in transforming a transport corridor into an economic corridor such as income level disparities among corridor inhabitants, processing industry allocation, standards, and certification.

- Bora (2023) explored the status of customs, transportation, and logistics in Cambodia and concluded that the customs clearance process does not differentiate among diverse shipment types, leading to inefficiencies and increased processing time and costs. Attempts to digitalize the process lack full implementation.

3.4. Manufacturing, trading and investing challenges

- All investments should be sustainable. Their economic impact should provide long-term benefits. Ecological impact should lead to as few negative consequences for the environment and inhabitants as possible. (Phyrum et al., 2007)

- Bordering SEZs in Cambodia and Thailand are facing issues in human resource exchange. Passports required to cross borders and paperwork to employ foreigners are hindering easy exchange. (Tangtipongkul et al., 2021) Malar (2014) notes that advanced border checkpoints between Thailand and Viet Nam have been initiated, but not yet fully finalized.

4. Overcoming economic corridor development challenges in Cambodia

Based on the identified challenges to economic corridors in Cambodia described above, the following recommendations may be made:

- Recommendations related to infrastructural challenges

Experts collectively agree that challenges related to infrastructure are of highest importance when creating economic corridors in Cambodia. In many cases they were the main motivation to establish the initiative and corridors in early phases. There is also agreement on the fact that since the founding phase of the corridors, substantial improvements have been made, especially related to the improvement, upgrade, and extension of the Cambodian road network. Ambashi et al. (2020) analyzed infrastructure development in the Mekong region, concluding that after reducing intra- and extraregional tariffs through the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement, Mekong countries will gradually advance infrastructure development and improve trading activities leading to economic benefit for Mekong region nations. Therefore, regional and subregional administrations should further extend efforts to improve infrastructure as a key challenge to growth in all socioeconomic aspects. In this case, infrastructure must not be limited to road networks, but should also include all relevant avenues of transportation (railroad networks, harbors, airports, waterways), communication (state-of-the-art data networks), electricity and water supplies, as well as wastewater treatment solutions. These recommendations are supported by the Comprehensive Master Plan on the Cambodian Transit and Logistics System 2023 – 2033 published by the Kingdom of Cambodia (2024). It comprises 94 projects related to road transportation, eight to railway transportation, 23 to river transport-ation, 20 to maritime transportation, and 20 to air transportation. (Kingdom of Cambodia, 2024)

In addition to this hard infrastructure, emphasis on improving soft infrastructure is needed for further positive development. Regional and subregional administration as well as the private sector should further improve education and skills training to acquire skilled staff. This is increasingly relevant following the aim to increase value added generated in Cambodia as well as to meet requirements from new technologies related to Industry 4.0. This is especially important according to Ambashi et al. (2020), who analyzed infrastructure development in the Mekong region, observing that activities must involve Industry 4.0 elements, such as “artificial intelligence, the internet of things, automation, and robotics” to increase long-term growth and economic success. Improving hard and soft infrastructure will have direct and indirect positive effects on other infrastructural challenges, such as the aforementioned difficulties resulting from size differences among nations, development levels, and socioethnic issues. - Recommendations related to institutional challenges

Market economies within the economic corridors follow different conceptual pathways, in part. As changes to this situation are unlikely, solutions to deal with it are advised. Local administrations should overcome challenges described to institutional challenges by strengthening interoffice awareness of motivation and need for economic corridors as well as among local residents. Adequate information and marketing strategies must be implemented to raise awareness and knowledge. Incentives given to potential investors should promote long-term engagement as well as high added value and product or service quality. Potential negative impacts from such activities, such as displacement of people, should be openly communicated, carefully decided, respectfully performed, and correctly compensated. Issues related to customs clearance should be overcome and the process fully digitalized. - Recommendations related to logistics service provider challenges

Several analyses conclude that custom clearance processes in the economic corridors in Cambodia are inefficient and outdated. Bora (2023) suggests a higher level of differentiation in the customs clearing process should be implemented to increase efficiency of the process and decrease process time and costs. All relevant processes should be paperless and fully digitalized. Facilitation or even elimination of such administrative processes may be seen in different regions internationally, setting potential examples for improvements in Cambodia and its economic corridor partners. - Recommendations related to manufacturing, trading, and investing challenges

As highlighted above, developments and investments should be sustainable. They should focus on long-term, qualitative, sustainable engagements. Manufacturers, traders, and investors should emphasize activities on such investments for the sake of sustainable growth as well as for inhabitants and the nation. Cross-border staff exchange remains an administrative issue. The government should simplify immigration and work permit processes. As already recommended for customs clearance processes, the cross-border process of exchanging staff should also be digitalized and paperless. - Recommendations related to potential extensions on economic corridors

- Stronger emphasis on border regions: Kuroiwa (2016) explored regional cross-border development strategies, finding that Cambodian firms operating in the border area with parent factories in Thailand have advantages, especially related to better access to suppliers and potential customers. Disadvantages must be overcome, especially related to human resources, recruiting procedures, and staff education. The Vietnamese government installed cross-border economic zones (CBEZs) to increase economic growth potential at border regions. (Ngoc, 2019) This strategy might be suitable for Cambodia, to allocate SEZs in the border region, and link them to neighbouring BEZs. Thailand has strong economic potential in its border regions, with more advanced infrastructure and higher local purchasing power. (Yagura, 2013) Thus, a similar strategy with Cambodia’s neighbor to the west might be beneficial.

- Extending the Belt and Road Initiative: Potential extensions to the SEC may result from activities by the Chinese government to further surpass development expressways in the GMS to try to connect this region to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). (Ishida, 2019) Muhammad et al. (2023) characterize the BRI as “a 21st century manifestation of the [historical] Silk Road”. As part of this initiative, the road network has been extended by hundreds of additional miles, although of varying quality. (Murg, 2022) The key motivation of this initiative is to link China to Western Europe by land using transcontinental railway networks and roads, but also to improve shipping routes, energy networks, and communication channels. (Jensen, 2022) Cambodia’s Rectangular Strategy supports the BRI, setting five priorities: policy coordination, connectivity improvement, trade activity support, boosted financial integration, and cultural connections. (CSHK, 2021) This initiative and its link to additional markets might lead to further opportunities for Cambodia with China, a significant economic partner. In addition to these additional opportunities, BRI-related concerns must be highlighted by criticizing intransparency and focusing on large-scale debt-finance infrastructure projects and corruption-related concerns. (Calabrese & Cao, 2021; Chheang & Heng, 2021; Jensen, 2022)

- Extending the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway: Another potential extension of the current SEC corridors might be a link to the India–Myanmar–Thailand Trilateral Highway (IMT Highway). This would require an extension to Cambodia, supporting the objectives of the MIEC (see sub-chapter NN) and facilitating trade, communication, and tourism, especially with Myanmar and India. (Mathur, 2021)

In conclusion, the economic corridor development in Cambodia positively impacted national development and economic growth. Future actions based on suggestions must be carefully aligned, rather than addressed individually. Economic corridor development will continue only if all recommendations are carefully considered.

5. Summary

Since the end of its civil war, Cambodia has experienced a phase of socioeconomic change. The transformation from a socialist-orientated to a liberal market has led to economic growth and increased wealth and stability. As part of this transformation, the nation (re)established international relationships and (re)joined global treaties and agreements. Its geographical location between the industrial centers of Thailand and Viet Nam also made it an important partner in (co)founding or joining economic corridors. Today, Cambodia is part of several international corridors, consisting of national SEZs, which according to the CADP have improved the job market and increased export of goods. (ERIA, 2022)

In a national context, the SEZs are highly significant, offering incentives in defined areas for FDIs, and aiming to increase international trade. Internationally, the Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS), covering wide areas of Cambodia, is the most important of its kind. In different subregions, it connects economic and industrial centers directly to neighbors in the north, east, and west, facilitating import and export activities. The SEC has also initiated and coordinated major infrastructure projects, with positive impacts transcending trade improvements. In addition to the SEC, the Cambodia-Laos-Viet Nam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA), Mekong-India Economic Corridor (MIEC), and Ayeyawady – Chao Phraya – Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS) benefit the Cambodian economy. The East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC) in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) does not pass through Cambodian territory directly, but leads through sections of Thailand, Laos, and Viet Nam, linked to northern Cambodia, benefitting the latter nation’s economy.

Yet challenges also hinder the efficiency of economic corridors, chiefly related to infrastructure, although SEC measurements have led to significant improvements. Issues are oftenest related to the transportation and electricity networks, communication structures, and warehousing facilities. Other difficulties are due to differing levels of development between Cambodia and its partners, difference in market structures, an overall low level of education and training, administrative and immigration issues, and complex, paper-based clearance processes.

Therefore, improvements are urgently needed in infrastructure and training, as well as administrative and clearance processes as potential extensions of current economic corridors are proposed.

References

- Akbas, B., Kocaman, A. S., Nock, D., & Trotter, P. A. (2022). Rural electrification: An overview of optimization methods. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 156, 111935.

- Ambashi, M., Buban, S., Phoumin, H., & Shrestha, R. (2020). Infrastructure Development, Trade Facilitation, and Industrialisation in the Mekong Region. In book: Subregional Development Strategy in ASEAN after COVID-19: Inclusiveness and Sustainability in the Mekong Subregion (Mekong 2030)Publisher: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

- Bora, E. (2023). RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS CUSTOMS, TRANSPORT, AND LOGISTICS IN CAMBODIA Supply chain management and Logistics at ACLEDA Institute of Business. Transport. 6.

- Brunner, H. P. (2013). What is economic corridor development and what can it achieve in Asia’s subregions?. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, (117).

- Calabrese, L., & Cao, Y. (2021). Managing the Belt and Road: Agency and development in Cambodia and Myanmar. World Development, 141, 105297.

- CDC (Council for the Development of Cambodia). (2005). Sub-Decree On The Establishment and Management Of the Special Economic Zone.

- CDC (Council for the Development of Cambodia). (2024 a, n.d.). Special Economic Zones. Online source retrieved 09.02.2024. https://cdc.gov.kh/sez-smart-search/

- CDC (Council for the Development of Cambodia). (2024b, n.d.). Poipet PP SEZ. Online source retrieved 24.04.2024. https://cdc.gov.kh/sez/sez-b/

- CDC (Council for the Development of Cambodia). (2024c, n.d.). Koh Kong SEZ. Online source retrieved 24.04.2024. https://cdc.gov.kh/sez/sez-a/

- CDC (Council for the Development of Cambodia). (2024d, n.d.). Phnom Penh SEZ. Online source retrieved 24.04.2024. https://cdc.gov.kh/sez/sez-phnom-penh/

- Chheang, V., & Heng, P. (2021). 15. Cambodian perspective on the Belt and Road Initiative. Research Handbook on the Belt and Road Initiative, 176.

- Chheang, V., & Wong, Y. (2014). Cambodia-Laos-Viet Nam: Economic reforms and subregional integration. 京都産業大学通信制大学院経済学研究会. ISSN 2188-0697. 1. 225–254 p.

- CPP (Cambodian People’s Party). (2023, December 6). Cambodia Encourages Acceleration of CLV Triangle Area Development.

- CSHK (2021). Training Pack Cambodia. Research Centre for Sustainable Hong Kong (CSHK). Applied Strategic Development Centre of City University of Hong Kong (CityU).

- DAN – Development Analysis Network. (2005). The Cross Border Economies of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Viet Nam.

- Dezan Shira & Associates. (2009, December 18). Viet Nam Opens Cross-Border River Trade with Cambodia. In: Viet Nam Briefing. Online source retrieved 09.02.2024. https://www.Viet Nam-briefing.com/news/Viet Nam-opens-crossborder-river-trade-cambodia.html/

- Duval, Y. (2008). Economic cooperation and regional integration in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). The United Nations. Trade, Investment and Innovation Working Paper Series. 02(08).

- ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia). (2009). Mekong-India Economic Corridor Development. Concept Paper

- ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia). (2015). The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan 2.0 (CADP 2.0): Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation. Research Project Report. 2014 (4).

- ERIA (Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia). (2022).The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan (CADP) 3.0: Towards an Integrated, Innovative, Inclusive, and Sustainable Economy. ISBN 978-6025-460-42-5.

- GDCE (General Department of Customs and Excise of Cambodia) – Department of Information Technology. (2024). Export Statistics by Top 20 Countries, January 2024 (Provisional).

- GDCE (General Department of Customs and Excise of Cambodia) – Department of Information Technology. (2024). Import Statistics by Top 20 Countries, January 2024 (Provisional).

- GIZ – Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH. (2023). Survey Report – Cambodia’s Attractiveness for EU Foreign Direct Investments. Report under the Project ARISE Plus Cambodia

- Guina, C. S. (2008). The GMS economic corridors. Regional Outlook, 84.

- Hatsukano, N., Kuroiwa, I., & Tsubota, K. (2012). Economic integration and industry location in Cambodia. In Economic Integration and the Location of Industries: The Case of Less Developed East Asian Countries (pp. 88-120). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Ishida, M. (2007). Evaluating the effectiveness of GMS Economic Corridors: why is there more focus on the Bangkok-Hanoi Road than the East-West Corridor?.

- Ishida, M. (2009). Special economic zones and economic corridors. ERIA Discussion Paper Series, 16, 2009.

- Ishida, M. (2019). GMS economic corridors under the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Asian Economic Integration, 1(2), 183-206.

- Ishida, M., & Isono, I. (2012). Old, new and potential economic corridors in the Mekong region. Emerging economic corridors in the Mekong Region, 8, 1-42.

- Isono, I. (2010). Economic impacts of the economic corridor development in Mekong region. Investment climate of major cities in CLMV countries, 330-353.

- Isono, I. (2019). Economic impact of new subcorridor development in the Mekong Region. Cross-border transport facilitation in inland ASEAN and the ASEAN Economic Community, 192-209.

- Jensen, C. B. (2022). Emerging Potentials: Times and Climes of the Belt and Road Initiative in Cambodia and Beyond. East Asian Science, Technology and Society: An International Journal, 16(2), 206-229.

- Kingdom of Cambodia. Ministry of Public Works and Transport (1999). Agreement Between The Government of The Kingdom Of Cambodia and The Government of LAO People’s Democratic Republic On Road Transport

- Kingdom of Cambodia. Ministry of Public Works and Transport (2007). Protocol For The implementation of The Road Transport Agreement Between The Government of The Kingdom Of Cambodia and The Government of LAO People’s Democratic Republic.

- Kingdom of Cambodia. Ministry of Public Works and Transport (2009). Memorandum of Understanding on Type and Quantity of Commercial Motor Vehicle for Implementation of The agreement and The Protocol Between The Government of The Kingdom Of Cambodia and The Socialist Republic of Viet Nam on Road Transport.

- Kingdom of Cambodia. Ministry of Public Works and Transport (2013). Memorandum of Understanding Between and Among The Government of The Kingdom Of Cambodia, The Government of LAO People’s Democratic Republic and The Socialist Republic of Viet Nam on Road Transport.

- Kingdom of Cambodia. (2024). Comprehensive Master Plan on the Cambodian Transit and Logistics System 2023 – 2033.

- Krongkaew, M. (2004). The development of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): real promise or false hope?. Journal of Asian Economics, 15(5), 977-998.

- Krongkaew, M. (2004). The development of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS): real promise or false hope?. Journal of Asian Economics. 15 (5), 977-998.

- Ksoll, C., & Brimble, P. (2012). Facilitating trade along the Southern Economic Corridor. Trade and trade facilitation in the Greater Mekong Subregion, 39.

- Kuroiwa, I. (2016). ‘Thailand‐plus‐one’: a GVC‐led development strategy for Cambodia. Asian‐Pacific Economic Literature, 30(1), 30-41.

- Kuroiwa, I., & Tsubota, K. (2013). Economic integration, location of industries, and frontier regions: evidence from Cambodia. Institute of Developing Economies (IDE). IDE Discussion Paper. 399.

- Malar, U. (2014). Initial Literature Review on Economic Corridor Impact on Rural Development in North-South Economic Corridor (NSEC): Case Study of Lungnamtha and Bokeo Provinces, Laos PDR.

- Mathur, S. K. (2021). Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), The India Myanmar Thailand Trilateral Highway and Its Possible Eastward Extension to Lao PDR, Cambodia and Viet Nam: Challenges and Opportunities, Integrative Report.

- Mekong Institute. (2017, n.d.). Southern Economic Corridor – Business Database & B2B Platform. Online source retrieved 08.02.2024. https://www.sec4business.com/about-us/about-project-and-project-team

- Mephokee, C., Roopsom, T., & Klinsukhon, C. (2014). Thailand-Cambodia Economic Cooperation under ACMECS. Thai Journal of East Asian Studies, 18(2), 1-11.

- Muhammad, F., Baig, S., Alam, K.M., & Shah, A. (2023). Silk Route Revisited: Essays and Perspectives on the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Beyond. China Study Centre Karakoram International University.

- Murg, B. J. (2022). Walking a fine line: How Cambodia navigates its way between China and Viet Nam. Southeast Asian Affairs, 2022(1), 126-137.

- National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. (2023). Economic Census of Cambodia 2022.

- Ngoc, A.Q.T. (2019). How the border economic zone in Viet Nam was developed: The case of Tay Ninh city in the border with Cambodia. Master’s thesis. University of Eastern Finland.

- O’Neill, A. (2023). Cambodia – Statistics & Facts. In: Statista – Economy & Politics – International. Published Dec 21, 2023.”

- Phi, V. T. (2012). Regional Development along Economic Corridors: Southern Coastal and Northern Subcorridors in Viet Nam. in: Emerging Economic Corridors in the Mekong Region. edited by Masami Ishida. Bangkok Research Center (BRC). 8.

- Phon-ngam, P. (2021). East-West Economic Corridor: A Route Of Economy And Friendship. Voice of Research. 9(4).

- Phyrum, K., Sothy, V., & Horn, K. S. (2007). Social and economic impacts of GMS Southern Economic Corridor on Cambodia. Research and Learning Resource Center of the Mekong Institute.

- Ratanasithi, S., & Jaroenwanit, P. (2012). Barriers to Border Trade along the Southern Economic Corridor: A Case of Thai-Cambodia Trade on the Border of Srakaew Province. GREATER MEKONG SUBREGION ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH NETWORK, 121.

- Sisovanna, S. (2011). Economic Corridors and Industrial Estates, Ports, and Metropolitan and Alternative Roads in Cambodia. Intra and Inter-City Connectivity in Mekong Region, Bangkok Research Center.

- Sisovanna, S. (2012a). A study on cross-border trade facilitation and regional development along economic corridors in Cambodia. Emerging Economic Corridors in the Mekong Region, BRC Research Report, 8.

- Sisovanna, S. (2012b). The Cambodia Development Triangle Area. In: Five Triangle Areas in The Greater Mekong Subregion. Emerging Economic Corridors in the Mekong Region, BRC Research Report, 11. Online source retrieved 09.02.2024. https://www.cpp.org.kh/en/details/363330

- Sophorndara, N. (2009). Trade and Transport Facilitation in Cambodia. Studies in Trade and Investment, 66, 133-145.

- Sotharith, C. (2007). How can Mekong region maximize the benefits of economic integration: A Cambodian perspective (No. 16). Cambodian Institute for Cooperation and Peace.

- Supatn, N. (2012). A study on cross-border trade facilitation and regional development along economic corridors: Thailand perspectives. BRC Research Report, (8), 41.

- Suthy, H. (2022). Inland Waterway Transport in Cambodia. National Workshop on Sustainable Maritime and Port Connectivity for Resilient and Efficient Supply Chains

- Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 6 September 2022.

- Tam, B. T. M. (2019). SEZ Development in Cambodia, Thailand and Viet Nam and the regional value chains. EEC Development and Transport Facilitation Measures in Thailand, and the Development Strategies by the Neighbouring Countries. BRC Research Report, 24, 87.

- Tangtipongkul, K., Srisuchart, S., Nuchmorn, N., & Vinayavekhin, S. (2021). Local economic development to support opportunities and impacts from special economic zones along the greater Mekong subregion southern economic corridor: Case studies in Kanchanaburi and Trat provinces. Thammasat Review, 24(1), 79-110.

- te Velde, D.W., Ouch, C., Hiev, H., Yang,M., Kelsall (2020). Fostering an Inclusive Digital Transformation in Cambodia. Research Report SET (Supporting Economic Transformation ).

- Thangavelu, S. M., Soklong, L., Hing, V., & Kong, R. (2023). Investment Facilitation and Promotion in Cambodia: Impact of Provincial-level Characteristics on Multinational Activities. ERIA Discussion Paper Series. 480.

- Viet Nam & Cambodian Government (Government of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam & Royal Government of Cambodia). (2009). Agreement on Waterway Transportation.

- Viet Nam & Cambodian Government (Government of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam & Royal Government of Cambodia). (2022). Joint Statement Between the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam on the Occasion of the Official Visit of H.E. Pham Minh Chinh, Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam to the Kingdom of Cambodia From 08 to 09 November 2022.

- World Bank. (2023). Enterprise Survey – Cambodia 2023 Country Profile. www.enterprisesurveys.org.

- World Bank. (2024). The World Bank In Cambodia – Overview. Last Updated: April 2024. Online source retrieved 24.04.2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cambodia/overview

- Yagura, K. (2013). Cambodia: The economic potential of the Thai border areas. In Border Economies in the greater Mekong Subregion. In: IDE-JETRO Series. pp. 107-132. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.