Economic Corridor Development in Myanmar

Developing Economic Corridors in Continental Southeast Asia: A Cross-Country Comparison (Myanmar)

Myo Nyein Aye, Ph.D.

Ministry of Transport and Communication, Myanmar

1. Introduction

Myanmar is bordered by five neighbouring countries: China to the north and northeast, Laos and Thailand to the east and southeast, and Bangladesh and India to the west. To the south, it faces the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal. Myanmar has a surface of 676,553 square kilometers (km2) with seven states, seven regions and one union territory, Naypyitaw. In 2021, the population was about 54.82 million (Myanmar Statistical Yearbook). Given the diversity of urban and rural dwellers, strong links are needed when designing and developing transport infrastructure for passengers and cargo. In addition, regional connections among neighbouring national markets must have improved supply chains and regional trade facilitation to enhance local and regional economic integration.

The corridor development strategy is vital for developing the economy nationwide. It should be formulated to maximize investment impact, by concentrating on investments in selected, prioritized, and coordinated projects along the targeted corridors to cover the entire nation and contribute to Myanmar’s development (JICA, 2018).

In the GMS Logistics Corridor prepared by Dr. Ruth Banomyong of Thammasat University, Thailand, four major functional levels of corridors are identified: transport; multimodal transport; logistics; and economic (Banomyong, 2008). These levels enable policymakers to better understand the functional level of corridors and determine development priorities.

In 2014, the National Transport Masterplan (NTMP) was studied and formulated with technical assistance and cooperation from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). It outlined a national development plan for the transport sector and offered guidelines for a long-term investment program for diverse transport projects in Myanmar to achieve economic growth targets by 2030 (JICA, 2014). The NTMP described transport corridors as covering all national regions with transport-related networks. Improved local and regional connectivity would expand trade and revitalize the national economy through urban and rural area networks.

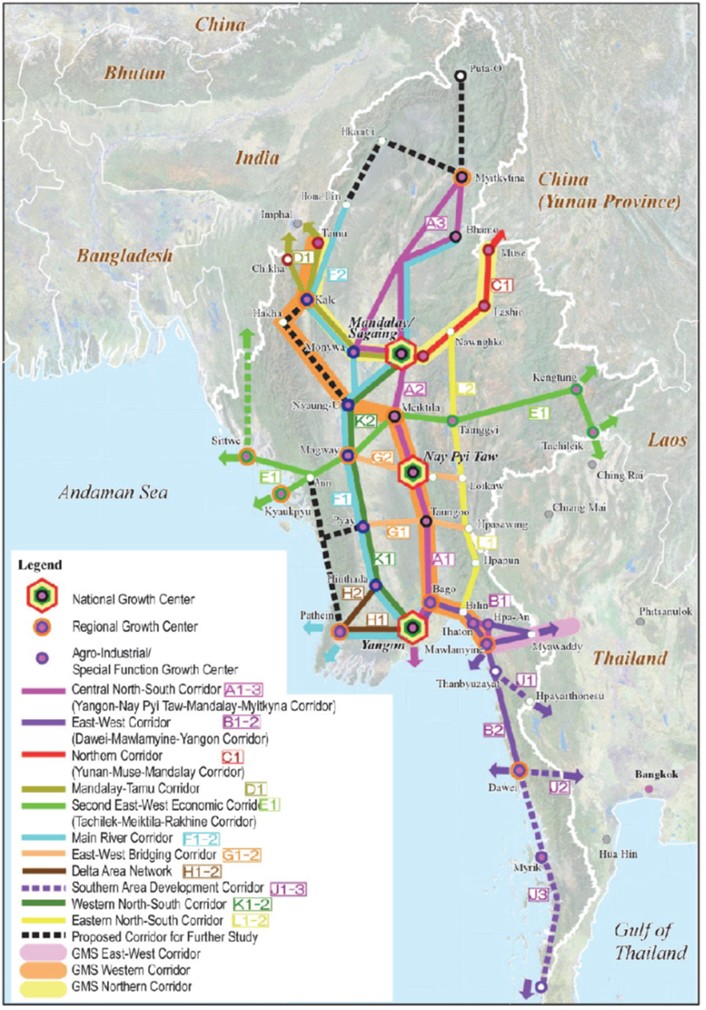

The Myanmar National Logistics Master Plan (NLMP) Study for 2018-2030, formulated in 2016, finalized in 2018 and launched in 2020, mainly based on the NTMP, transformed extant transport corridors to multimodal logistics corridors. In the master plan, six major logistics corridors were proposed, three of which linked the two major economic growth poles in Myanmar: the GMS East-West Economic Corridor and Northeastern India. In addition, two water and maritime related corridors are situated along the Ayeyarwaddy and Chindwin Rivers, and along the entire 1,700 km long coast of Myanmar. For transit trade, the logistics corridor is also formulated for horizontal traversal of central Myanmar.

2. Economic Corridor Development in Myanmar

Based on extant transport corridors and individual networks for different transport modes, their effective, integrated use with multimodal transport is the first step towards developing corridor logistics and supply chain networking. By improving logistics performance along local and regional multimodal transport corridors, the ensuing logistics corridors will physically and institutionally facilitate efficient movement and storage of freight, passengers, and related information. Ultimately, logistics corridors must be urgently upgraded and transformed to economic corridors to meet the needs of national economic development and sustainability. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) also proposed that corridor development would provide a spatial focus for transporting improvement, connecting growth centers, and catalyzing development of surrounding locations to open opportunities for different types of investment while promoting synergy and impacting the regional economy (ADB, 2010).

2.1. National Economic Corridor Development

The transport infrastructure development and corridor approach are basic, essential requirements of national economic corridor growth. The concept of economic corridors was introduced in the National Spatial Development Framework (NSDF), establishing a hierarchy of cities and nationwide connectivity by the Department of Urban and Housing Development (DUHD), Ministry of Construction (MoCon). NSDF was based on international, national, regional and city development policies and transport networks, including Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)/transnational highway and railway corridors, Asian highways, Myanmar national expressways and other major roads, and railways and major rivers with an inland waterway function required to underpin and strengthen transport and economic linkages between strategic activity hubs (JICA, 2014).

Understanding the transport infrastructure may contribute to economic corridor development. The Myanmar National Transport Master Plan (NTMP) was based on the NSDF and finalized in 2014. The NTMP approach to develop a corridor-based transport infrastructure described and identified priority corridors and necessary transport infrastructure and services along designated corridors (JICA, 2014).

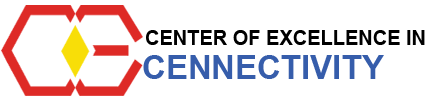

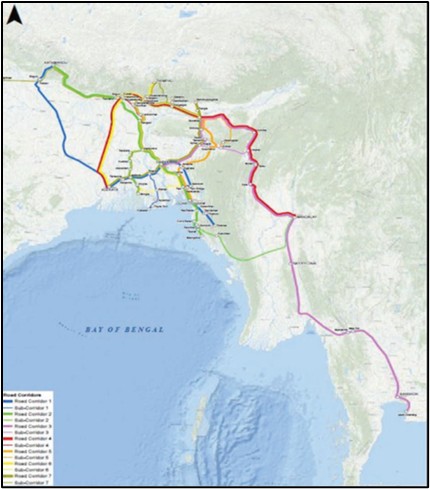

In NTMP, twelve development corridors connecting strategic activity hubs were identified and selected according to whether corridors embraced significant urban economic activities, such as strategic transport networks, strategic transport facilities (ports, airports, rail stations and interchanges), industrial zones, agroindustrial centers, international and national networks and major nodes for all transport modes. Those corridors are illustrated in Figure 1.

In 2018, based on extant transport corridors, a corridor-based logistics infrastructure development plan was formulated in the National Logistics Master Plan (NLMP), identifying logistics corridors interconnected at potential local transport routes and regional linkages. Those logistics corridors are listed as below and shown in Figure 2:

- Myanmar-India

- North-South

- South-East

- Main River

- Trans Myanmar

- Coastal Marine

Figure 1 National Spatial Development Framework and Development Corridors

Source: NTMP (2014)

Figure 2 Logistics Corridor Formulated by NLMP (2018)

Source: NLMP (2018)

2.2. Bilateral Economic Corridor

Since 1997, when Myanmar joined the ASEAN community, it has approved economic integration and unification by cocreating and operationalizing the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC). Myanmar is located at the center of three economic growth poles: Bangladesh and India to the west, China to the north, and the ASEAN and GMS member countries (including Laos and Thailand as neighbours) to the south.

2.2.1. India and Myanmar

Bilateral relations between India and Myanmar are positive because of geographical location, proximity, and shared history. To improve cooperation in the transport and logistics sectors, the Motor Vehicles Agreement (MVA) facilitated cross border movement of vehicles between two countries, as discussed since 2015. In 2023, the pending discussion was restarted internationally and an agreement was drafted. By the end of 2024, a final draft of MVA is anticipated to be resent to India through diplomatic channels. The MVA should enhance development of economic corridors between India and Myanmar.

2.2.2. Bangladesh and Myanmar

Bangladesh and Myanmar have worked to deepen their relationship and mutual cooperation in diverse sectors. Both nations may benefit from collaboration in shared areas of common developmental challenges. Currently, there are no specific bilateral agreements for transport or economic corridors. But the two nations bridge South Asia and Southeast Asia. In addition, Bangladesh and Myanmar are founding members of the subregional Bay of Bengal Initiatives for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) group. Both countries have participated in regional economic corridor development through BIMSTEC.

2.2.3. China and Myanmar

Myanmar and China benefit from close cooperation in a rapidly developing cooperative relationship of long date. In September 2018, Myanmar signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) on Jointly Building the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) with China. The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) is one strategic infrastructure project of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aimed at connecting Myanmar’s major economic centers to China (paradigmshift, 2023).

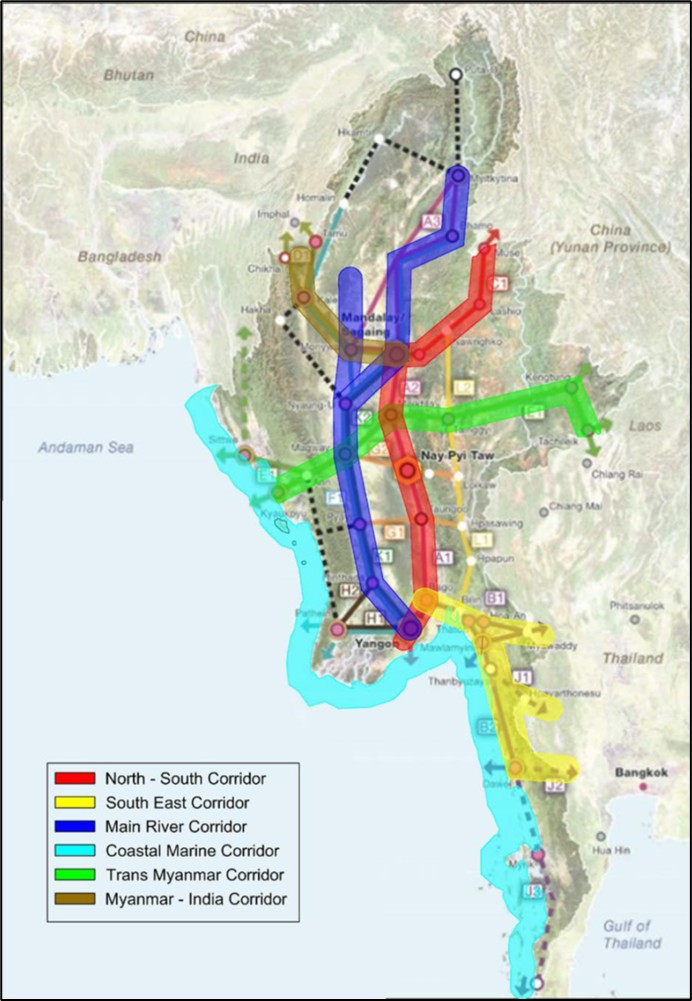

This corridor will enhance connectivity between Myanmar and China. Over the past decade, China has shown a strong commitment to investing in infrastructure projects in Myanmar through the BRI. CMEC will create a route connecting the Indian Ocean with China’s Yunnan Province to establish a consistent supply chain platform for trading essential resources between Myanmar and China. This strategic development is expected to benefit China by addressing internal development goals (Myers, L, 2020). As part of the CMEC strategic infrastructure development program, diverse infrastructure projects are being undertaken in Myanmar, including the construction of new road networks, a high speed railway line, and deep sea ports located along the coastal line of Myanmar which may been seen as a Y-shaped corridor linking vital national commercial hubs with China’s Yunnan region (Ahmad, W, 2024).

In addition, the Kyaukphyu Deep Sea port is being developed to provide direct access to the Indian Ocean, along with the Muse-Mandalay railway to connect key regional trade routes. The gas and oil pipelines may be seen in Figure 3, providing a crude oil supply source for Yunan province. Together with basic CMEC infrastructure development, Myanmar-China bilateral trade has been enhanced, reaching around $2.16 billion between April 2022 and January 2023 with China as Myanmar’s leading trade partner (Ahmad, W, 2024).

Figure 3 Cross-country gas and oil pipelines to support Yunan, China

Source: Vivekananda International Foundation

To facilitate cross-border transport between China and Myanmar as GMS member countries, a draft MoU on initial implementation of cross-border transport has been prepared with reference to the Myanmar-Thailand IICBTA. This agreement was reached during the Third Joint Committee Retreat and Related Meetings for the Cross Border Transport Facilitation Agreement (CBTA) held on 17-18 December 2019 in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. China proposed an MoU (draft) on Initial Implementation of the GMS CBTA (IICBTA) between China and Myanmar in January, 2020. Negotiations between Myanmar and China finalized the agreement. After completion of the process, Myanmar and China will sign an MoU for IICBTA under GMS CBTA framework.

2.2.4. Lao and Myanmar

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR) and Myanmar will explore opportunities to enhance tourism and transport through bilateral cooperation and a draft MoU on initial implementation of cross-border transport between Myanmar and Laos would be prepared with reference to the Myanmar-Thailand IICBTA. To prepare and draft the MoU, comments and suggestions from related ministries and departments would be solicited to comply with GMS CBTA framework and extant domestic laws, rules and procedures. Myanmar has other opportunities to facilitate regional transport and trade by using the Laos–China Railway (LCR) which runs about 1,000 kilometers from Vientiane, near the Thai border, through Luang Prabang to Kunming in Yunnan province, China. The start of the IICBTA is an opportunity for using the Trans-Myanmar corridor for boosting cargo and passenger flow between Laos and Myanmar.

2.2.5. Thailand and Myanmar

The Myanmar-Thailand MoU on Initial Implementation of Cross-Border Transport Agreement was signed on 13 March 2019. According to IICBTA, by 2020, a Cross Border Transport Operator License was issued to 73 vehicles and 70 trailers from seven companies. In 2020, cross-border transportation was initially operated by one company from Thailand and three from Myanmar. However, due to the Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic, cross-border transportation was temporarily suspended.

The agreement relates to transportation of goods and passengers between Mae Sot and Myawaddy border crossing along the Eastern-Western Economic Corridor (EWEC), as well as the extension of the route to the Thilawa Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in Myanmar and Laem Chabang Port. There are additional plans for building an Endu-Thaton Road, with the Thai Department of Highways helping Myanmar to upgrade the road. The Endu-Hpa-An Road spans 24 kilometers (km), while the Hpa-An-Thaton Road is 36 km long, serving as an extension and improvement to the EWEC (Sawasdee, 2024).

In 2024, meetings and discussions between Myanmar and Thailand promoted friendly relations, enhancing economic cooperation through economic corridors, boosting trade, improving border trade measures, expanding business and investments, ensuring a smooth flow of export and import processes, fostering the tourism sector, and upgrading infrastructures (MOI, 2024).

Myanmar and Thailand are at the center of three large consumer markets: India, China and the ASEAN community. Both countries can enhance transport and logistics corridors into economic corridors.

2.3. Regional Economic Corridor Development

The corridor development approach, primarily aimed at GMS countries, has been designed to suit the transport sector and logistics system development in Myanmar. The foundation of economic corridors in the Indochina Peninsula has been prepared by the ADB based on GMS development strategy.

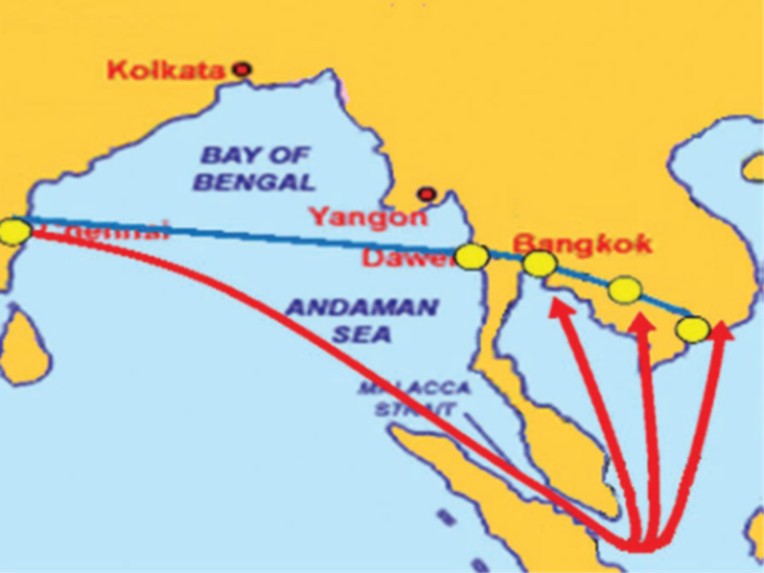

Three main economic corridors in the GMS comprise: The North-South Economic Corridor (NSEC) through the whole region, principally connecting Myanmar and Yunnan province, China. Mawlamyaing, Myanmar and Da Nang,Viet Nam serve as vital points in the EWEC, which also passes through Thailand and Laos. However, to improve transport and logistics connections, the increased cargo traffic resulting from dispersing production facilities across major regional cities must be handled (JICA, 2018). At the western sea exit of the Southern Economic Corridor (SEC), Dawei Deep Sea Port and SEZ projects become key infrastructure for Myanmar and the GMS, potentially playing a significant role in developing economic corridors. With the anticipated deep-sea port, an area of about 20,000 hectares, and easy access to Thailand, Dawei may become a logistics hub. This potential may be fully realized after economic corridor development with transport and transshipment of trade between the two countries. Expanding GMS corridors as planned may strengthen links between GMS nation capital cities (ADB, 2018).

Another economic cooperation bloc is BIMSTEC, a regional organization for nations on the littoral and adjacent areas of the Bay of Bengal. The Framework Agreement on BIMSTEC Free Trade Area (FTA) was signed for economic cooperation on 8 February 2004 to liberalize, promote, and facilitate trade in goods and services, investments, and wider economic cooperation (BIMSTEC, 2024).

Transport connectivity is a fundamental requirement for regional economic development and cooperation. BIMSTEC connects South and Southeast Asia, a region with a population of about 1.5 billion and a gross domestic product (GDP) of $2.7 trillion. In 2022, the BIMSTEC Master Plan for Transport Connectivity (the Master Plan) was launched with a framework for organizing a set of policies, strategies, and projects to realize a shared vision of peace, prosperity, and sustainability which are basic essentials for regional economic development and cooperation (ADB, 2022).

The Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) conceptualized the Mekong-India Economic Corridor as a step towards integrating the East Asia and East Asia Industrial Corridor (EAIC) to link India with the Mekong region (ERIA, 2009). It also passes through the Dawei Deep-Sea Port area with a potential economic corridor linking BIMST-EC and GMS regional members.

Figure 4 Economic Corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion

Figure 5 Schematic Map of Development of BIMST-EC Road Corridors

Figure 6 The Proposed Mekong–India Economic Corridor

2.4. International Economic Corridor Development

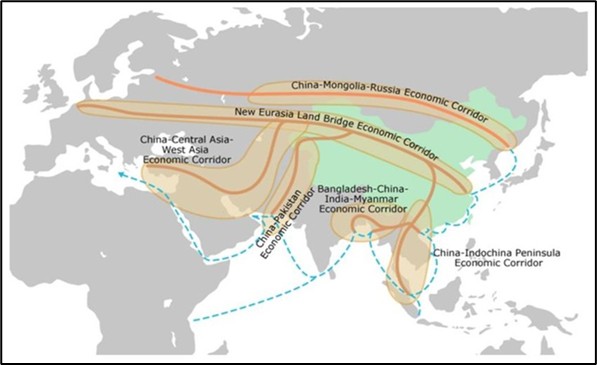

The RCEP, a free trade agreement negotiated among ten ASEAN member states and six dialogue partners since 2012, was signed by ten ASEAN countries and five other nations after India withdrew from negotiations in 2019. The agreement, which includes China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, represents 2.2 billion people, nearly 30% of the world’s population, with a combined GDP of US$26.2 trillion. It accounts for around 30% of global GDP and 28% of global trade, making it the largest free trade arrangement in the world (Thaibiz, 2020). Since 1 May 2022, Myanmar has participated in the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), with the establishment of a new maritime trade route between Guangxi and Yangon connecting ports in RCEP member states. The strategic ports of Yangon and Kyaukphyu play key roles in China-led projects, making Myanmar a focal point in China’s road-sea transportation corridor (ISP, 2023)

Geographically, Myanmar holds a significant position in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), situated at the crossroads of South Asia and Southeast Asia, as well as between the Indian Ocean and China’s landlocked Yunnan province. Similar to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) linking Xinjiang to Karachi and Gwadar, the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) to the Bay of Bengal is reshaping economic dynamics on India’s eastern front (Aspireias, 2023).

As part of the BRI, the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM–EC) also proposed to connect eastern China with South Asia, extending to Southeast Asia by using different transport modes for better economic and cultural connectivity (Karim, M.A. & Islam, F., 2018)

Figure 7 The Belt and Road Initiative: Six Economic Corridors Spanning Asia, Europe, and Africa

Figure 8 Map of BCIM–EC in South and Southeast Asia

3. Challenges to Economic Corridor Development in Myanmar

In October 2012, the ADB conducted an initial assessment of Myanmar’s transport sector, highlighting key challenges, opportunities, and priority needs. This assessment was part of background information for ADB’s interim country partnership strategy in Myanmar. The assessment also serves as a resource for the JICA study team to pinpoint strategic issues and develop corresponding strategies. By incorporating updated information from 2013 and consulting with specialists in Myanmar’s transport sector, this assessment may be further enhanced to support JICA national efforts. ADB assessments highlight key issues in Myanmar’s transport sector, including fragmented and overlapping institutional structures, no comprehensive transport sector strategy, a lack of rigorous cost-benefit economic analysis to prioritize infrastructure investments, the need for capacity building using extant subsector institutions and officials, limited involvement of the private sector, and the poor condition and insufficient coverage of the lower level road network, leading to inadequate access to basic services for local communities (JICA, 2014). ADB observed several challenges to overcoming obstacles impeding transport sector issues, which may be seen as basic challenges to economic corridor development.

As a member of the GMS, Myanmar has been facing similar challenges to economic corridor development and sustainability. Cuong listed six key constraints to maximizing potential benefits from three GMS economic corridors (Cuong M. Nguyen (2016)). Related challenges for Myanmar follow:

- Incomplete cross-border and multimodal infrastructure network, especially for the feeder road network connecting production and trade hubs with the as yet undeveloped corridor.

- The cost of business and trading with Myanmar varies widely and remains comparatively high due to non-tariff measures, inefficient cross-border procedures, lack of a customs transit system, and poor logistics services.

- Tightly regulated transportation routes to facilitate cross border road transport by trucks and other vehicles.

- Substandard freight forwarding and delivery in Myanmar, especially in packaging, retail, and cooling facilities. In addition, inadequate infrastructure and poor-quality road networks are constraints for development of GMS economic corridors.

- Substantial flows of informal trade and low-skilled labor have significantly impacted economic corridor development socioeconomically.

- Myanmar’s border areas are comparatively neglected by its neighbours: China, Laos, and Thailand.

In terms of BCIM economic corridors, Myanmar was initially seen as a primary goods exporter and inexpensive labor provider. But, regional instability at border areas creates challenges for long-term investment and sustainable development of economic corridors (Karim, M.A. & Islam, F., 2018).

Generally, potential challenges to economic corridor development may be categorized under infrastructure; institutional; logistics service providers; and manufacturing, trading and investing challenges.

3.1. Infrastructure Challenges

In addition to being transport connections along which passengers and goods are transported, economic corridors are integral to the economic fabric and relevant stakeholders (Brunner H. P., 2013). Transport and related infrastructure development and associated challenges are most important to overcome for the success and sustainability of economic corridors.

3.1.1. Transport (road/rail/river/coastal/maritime and air)

Supporting the ongoing economic and social growth in Myanmar as a member of ASEAN poses numerous challenges for the land transport system. Coping with the increasing number of vehicles, particularly 2-3 wheelers, rising freight volumes, and mobility demands of expanding urban populations is difficult. As railways and inland waterways currently play a minimal role in Myanmar, it is likely that the dominance of the road sector will persist in the near future (JICA, 2018)

To enhance competitiveness of the ASEAN logistics industry, several challenges must be addressed beyond 2015 in terms of transport facilitation. Establishing a safe and secure interstate transport system is essential for boosting ASEAN global competitiveness. Accelerating implementation of three framework agreements on transport facilitation, as well as the ASEAN Strategic Transport Plan (ASTP) and the Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity (MPAC), is necessary to reduce trucking dwell times at national borders and lower the costs of moving goods between countries regionally. This is a key element in achieving the vision of a “single market and production base” as outlined in the AEC Blueprint, and collaboration with trade facilitation implementation bodies is necessary to achieve this goal (JAIC, 2018).

Currently, the sole international port in Myanmar is Yangon port. It has 48 wharves which can accommodate 48 ocean vessels at a time (MPA, 2023). Yangon port is a river port with a draft limitation of about 9.6 m to 10.5 m according to tide times. From 2016 to 2020, the container throughput of Yangon port reached over 1 million TEUs, after the Covid-19 pandemic, it could handle only 695,099 TEUs in 2021, 855,070 TEUs in 2022, and 761,557 TEUs in 2023.

ADB study statistics indicate that Myanmar’s investment in transport sector infrastructure development has been inadequate. Between 2005 and 2015, transport sector investments were 1.0%–1.5% of the GDP (ADB, 2016). ADB also highlighted challenges still being faced:

- 20 million people without basic road access.

- 60% of highways and most rail lines in poor condition.

- In terms of road safety, 4,300 road fatalities in 2014, doubling mortality rates in 2009.

- Over the past four years: the vehicle fleet has doubled and the paved highway network has increased by 35%. Travel in Yangon has become two to three times slower and public transport operators have lost 35%–65% of the market.

- $60 billion in transport infrastructure investments is required for 2016–2030

- Road user fees cover only one third of infrastructure costs.

- Railway fares compensate only half of operational costs.

3.1.2. Other Facilities (such as dry ports/warehouses/DC/fulfilment center)

Myanmar developed dry ports in Yangon and Mandalay in accordance with the Intergovernmental Agreement on Dry Ports by UNESCAP. The first dry ports were officially launched in January 2019. The two dry port operators are still striving to achieve seamless movement of cargo to and from Yangon port and both dry ports. Upgrading of the Yangon-Mandalay rail line and other institutional framework is needed to cope with incoterms.

There are insufficient bonded warehouses and a high share of general cargo, leading to major congestion and long clearance processes at the Yangon port area (JICA, 2018).

3.2. Institutional Challenges

In 2011, major economic, social, and political transformation occurred in Myanmar after lengthy isolation in many sectors including economics. The foreign exchange system and telecommunications sector were revamped, government budget allocations for education, health, and infrastructure increased, and legal, regulatory, and institutional frameworks for foreign investment overhauled (ADB, 2019). According the ADB study, key development challenges since 2012 include improving access to basic services, particularly in conflict areas; ensuring infrastructure access and connectivity for robust economic growth; creating a labor force that meets labor market demands; building a dynamic and resilient private sector; mitigating environmental, climate change, and disaster risk; promoting rural development and agriculture; and strengthening public sector institutions and governance (ADB, 2019).

Several common challenges to economic corridor establishment, development and management were listed by Mutangadura from UN-OHRLLS (Mutangadura, G., 2021):

- Challenges in economic corridor establishment

- Identifying and designating corridor routes;

- Preparing, negotiating, adopting and ratifying corridor agreements;

- Funding construction/ rehabilitation of existing infrastructure gaps; and

- Establishing corridor management institutions (CMIs)

- Challenges in economic corridor development

- Initial financial resources to launch CMIs: procuring staff, equipment and office facilities, applying for grant funding;

- Enhancing infrastructure interoperability in areas such as discordant railway gauges – handled through provision of transshipment facilities and border terminals;

- Lack of harmonized customs procedures – request technical support from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) or the World Customs Organization (WCO);

- Lack of harmonized documentation – request support or learn from other corridors

- Challenges in economic corridor management

- Lack of skilled human capital/ staff for the CMI to undertake mandates of corridor training and resource mobilization;

- Lack of funds for approved annual budgets for the CMI – innovative resource mobilization;

- Delays in receiving and processing operational and planning data from service providers (ports, railways, roads, pipelines and transporters), infrastructure providers, regulatory/ oversight agencies – community charter; and

- Balancing the interest, governments and their regulatory agencies – ensuring participation of stakeholders

3.2.1. Domestic Rules and Regulations

For economic corridor development, interrelated institutions are the Myanmar Investment Committee (MIC) for foreign investments in transport and financial sectors; Ministry of Transport and Communications (MOTC) for developing the transport industry and communications sectors; Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations (MIFER) and Foreign Economic Relations Department (FERD) for development partners and foreign direct investment (FDI) issues; and the Ministry of Construction (MoCon) for building road infrastructure. Each has their own related laws, rules, regulations, and notifications.

Some large projects such as Kyaukphyu Special Economic Zone (KPSEZ) and Dawei Special Economic Zone (DSEZ) have separate ministerial level organizations to regulate and monitor development progress.

In 2018, after signing an MoU between Myanmar and China for the China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), the Implementation Committee for CMEC was formed with the union minister for planning and finance as chairperson. The committee has 12 cooperative working groups including for project development and transport. Each has a separate annual meeting with its Chinese counterpart.

3.2.2. Bilateral Rules and Regulations

For development of economic corridors between proximate countries, individual agreements, MoUs, or contracts bind both parties. Under the umbrella agreement of GMS CBTA, the MoU for IICBTA with Thailand was signed before the Covid-19 pandemic, while MoUs with China and Laos are ongoing processes to be finalized in the near future.

As mentioned before, an agreement for economic corridor development between Myanmar and China was signed in 2018 with many obligations to fulfill to implement the CMEC for both countries. Under the basic framework of CMEC, featuring bilateral discussions, joint contributions and mutually shared benefits, Myanmar must strive to develop an economic corridor with China.

Two bilateral mechanisms for trade between Myanmar and India are the Joint Trade Committee and Border Trade Committee. Kaladan Multimodal Transit Transport Project is the most significant connectivity initiative for trade and transport as well as a potential bilateral economic corridor (Embassy of India, 2022). But that project has been stymied due to local security issues.

Myanmar has bilateral trade agreements in Asia with India, Bangladesh, China, Laos, Thailand, Viet Nam, Malaysia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and South Korea, as well as with some Eastern European countries (PFS, 2024). For development of related economic corridors, local government engagement is a key challenge to overcome.

3.2.3. Regional rules & regulations

Myanmar has signed regional trade and economic development agreements with ASEAN, GMS and BIMST-EC. In 2005, Myanmar signed the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Multimodal Transport (AFAMT), ratifying it in 2015. To fully exploit multimodal transport, several domestic procedures and steps must be followed, such as organizing a national competence body and establishing a standard operating procedure (SOP) for issuing licenses and permits for local and foreign logistics service providers and multimodal transport operators (MTOs). Other ASEAN cooperation agreements related to transport include the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Facilitation of Transit of Goods, signed in 1998, and the ASEAN Agreement on the Facilitation of Inter-State Transport, signed in 2009.

3.2.4. Multilateral Rules & Regulations

As an ASEAN member state, Myanmar participates in all intra-ASEAN agreements as well as multilateral free trade agreements with several dialogue partners such as China, India, Japan, and South Korea. In 1998, Myanmar became involved in the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) to eliminate all tariff lines by 2018. To implementation the agreement, challenges included being in line with local rules and regulations, lack of trade and transport infrastructure, and the requirement to perform capacity building.

3.3. Logistics Service Provider Challenges

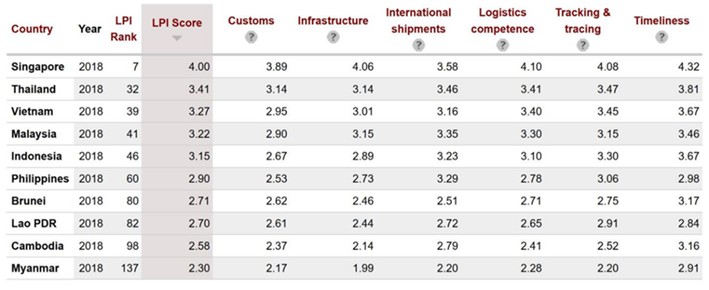

According to the logistics performance index (LPI), Myanmar rates as logistics unfriendly. For the final LPI measurement of 2018, Myanmar was in 137th place, the worst performance in the ASEAN community. Improvement would require international cooperation.

With political instability and the current financial and trade policy situations in Myanmar, the logistics service industry has suffered, leaving the market disorganized.

Several challenges remain to enhancing competitiveness of the ASEAN logistics industry and establishing a safe, secure interstate transport system to improve Myanmar and ASEAN world competitiveness (JICA, 2018). Myanmar must develop logistics-related hard and soft infrastructure to cope with regional trade and transport as essential supply chain platforms for developing economic corridors.

Figure 9 Logistics Performance Index (LPI) for ASEAN member countries in 2018

The JICA study team highlighted weaknesses and challenges for developing the logistics industry in the Myanmar National Logistics Master Plan study report (JICA, 2018):

- Waiting times for customs clearance and trans-loading operations at border areas remain long due to primitive cross-border facility handling capacities.

- National road network and diversification of road links with neighbouring countries are inadequately developed to meet trade and transport traffic demands.

- Low capacity and efficiency of truck terminals for land transport and coastal shipping.

- Absence of laws and regulations supporting logistics system modernization.

- Human resources shortfalls, especially due to migration of inhabitants to neighbouring countries.

- Fragmented, disorganized private sector transport and logistics companies.

3.4. Manufacturing, Trading and Investing Challenges

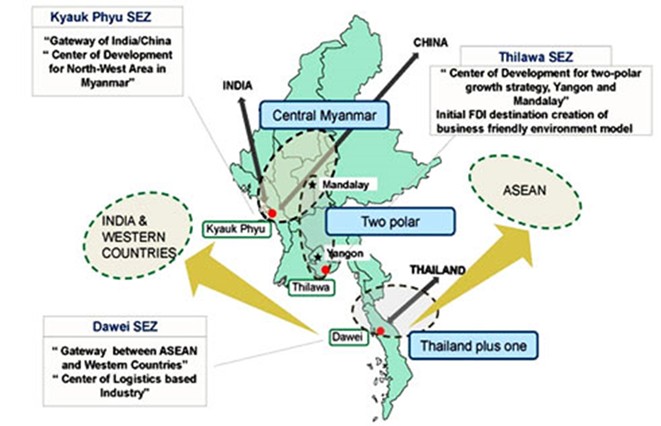

According to the Special Economic Zone Law enacted in 2014 with rules published in 2015, there are three SEZs in Myanmar: Thilawa SEZ in Yangon Region, Kyaukphyu SEZ in Rakhine State and Dawei SEZ in Thanintharyi Region. Each is managed by a separate central body, central working body, and management committee for implementation (DICA, 2024).

Thilawa SEZ is only one still functioning and attracting investment and manufacturing with comparative advantages of effective waste water management, clean water supply, land transportation system, Yangon Port (Thilawa area) near the economic zone, business network connections, power supply and low-wage workers. Yet some challenges remain for firms: long commuting times, recruitment nearby of qualified factory engineers, semi-skilled workers and office workers, and political instability (Aung, N. H., 2022). Kyaukphyu and Dawei SEZs have potential for manufacturers, traders, and investors, but are in the developmental negotiation stage.

Figure 10 Special Economic Zones in Myanmar

Source: Dawei SEZ

According to trade statistics, the total average annual trade volume is about 30 billion USD (MoCom, 2024) in normal and border trade, lower than neighbouring countries.

4. How to Overcome Economic Corridor Development Challenges

Economic corridors development is essential for nations, regions, and multinational associations as well as development partners and international institutions. In 2022, ADB and BIMSTEC signed an MoU for cooperation in five areas: transport connectivity and financing; energy connectivity and trade; trade facilitation; tourism promotion; and economic corridor development (ADB, 2024). This suggests that economic corridor development is a significant issue, with transport and trade connectivity.

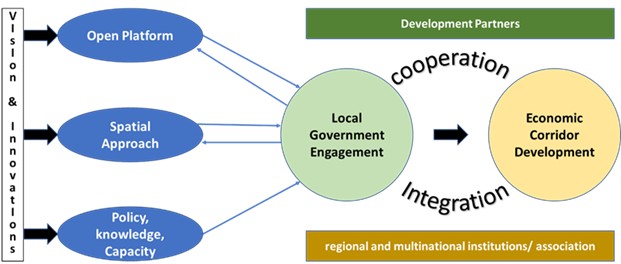

Strengthening local government engagement in regional and multinational institutions/ associations is essential for promoting economic corridor development. The GMS Secretariat noted three GMS 2030 cross-cutting areas of innovation that are central to increased local government engagement: a) transforming GMS into an open platform; b) enhanced spatial approach in GMS operations; and c) fostering dialog, knowledge sharing and capacity building among key stakeholders (GMS, 2024). Based on that concept, local government engagement is central, together with enhanced integration and cooperation with regional and multinational institutions/ associations and developments partners to overcome economic corridor development challenges.

Figure 11 Mechanism for developing economic corridors

Source: Author, modified from the GMS SecretariatFigure

Myanmar has different integrated economic corridors with neighbouring countries, regional blocs/associations, and multinational organizations. Different corridors have distinct geographic perspectives, with individual development challenges and potential issues.

The GMS recommends that to strengthen local government engagement and participation, extant economic corridor forum (ECF) institutional mechanisms should be used. To achieve attractive, effective forums, local governments must engage with several development partners for technical and financial consulting and assistance and potential contributions (GMS, 2024a).

To strengthen local government engagement for developing economic corridors:

- Using the extant Economic Corridor Forum (ECF) mechanism, close coordination between central governments shall enhance local Myanmar government engagement.

- Central governments and local authorities should collaborate to promote public servant performance in local government administrations.

- Varied execution of the three sovereign powers – executive, legislative, and judicial – in local governments across member countries of designated economic corridors, as influenced by diverse political systems, impacts local government engagement in regional and multinational institutions/ blocs/ organizations.

- Member countries should address potential obstacles by consulting and collaborating with development partners.

- ECFs shall implement subcorridor initiatives to boost local government engagement.

- National road networks and diversification of road links with neighbouring countries are inadequate for trade and transport traffic demand.

Challenges with infrastructure; institutions; logistics service providers; and manufacturers, traders and investors are interrelated and solutions must be holistic and integrated.

Infrastructure development, especially for transport and logistics, is vital for general national development, including trade and connected economic corridors. To improve transport and logistics related infrastructure planning, the Myanmar National Logistics Master Plan (MLMP) 2018-2030 offers the best guidelines for now and the immediate future. MLMP lists 187 projects, of which 22 are soft components and 165 hard components. Of the soft components, six are for logistics, one for roads, five for railways, two for waterborne transport, and eight for inland waterways. Most improve laws and regulations for different transport modes as well as study and enhancement programs. Of hard components, 14 are for logistics, including new truck terminals nationwide and building multimodal logistics complexes in Yangon, Mandalay and Bago; 56 for roads, including upgrading and improving major transport routes for trade and economic corridors; 24 for railways, including Mandalay – Muse and Mandalay – Tamu New Railway Line (a rail link between India and China through Myanmar), and inland container depots (ICDs) proposed by UNESCAP to facilitate trade; 12 for waterborne transport, including improving coastal ports for international vessels; 33 for inland waterway transport, including the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project; and 26 for aviation, including upgrading international airports for facilities handling air cargo. Among 167 hard component projects, prioritization is according to regional connectivity, domestic connectivity, economic benefit due to increased cargo transport efficiency, and consistency with national development policies (JICA, 2018). Each project has its own timeline, development schedule, and potential funding sources up to 2030. If the transport and logistics infrastructure may be developed, economic corridor development infrastructure challenges should be resolved accordingly.

Among diverse economic corridors with Myanmar, the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) is the most successful, despite some complications. Institutionally, CMEC may be seen as an example for other economic corridors in forming an implementation committee and related working groups, and reasonably empowering the teams to encounter challenges for economic corridor development.

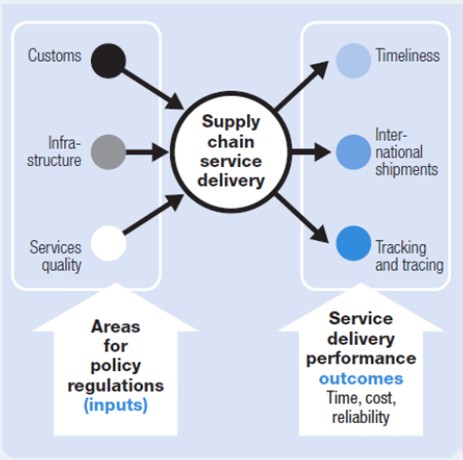

To improve competency of logistics services providers, policy recommendations and regulation authority are essential. Six components for improving the logistics performance index (LPI): a) customs and border management clearance efficiency; b) trade- and transport-related infrastructure quality; c) ease of arranging competitively priced international shipments; d) logistics service competence and quality; e) ability to track and trace consignments; and f) frequency with which shipments reach consignees. Among those, custom, infrastructure and service quality are necessary for improved supply chain service delivery (World Bank, 2023). With heightened logistics performance, economics corridor challenges may be overcome.

Figure 12 Input and outcome LPI indicators

Source: World Bank (2023)

To develop an economic corridor, manufacturers, traders and investors are also indispensable for promotion and allure. Investment weather must be managed favorably and sustainably as the highest priority for improvement. Economic corridors should link production centers, including manufacturing hubs, industrial clusters, and economic zones; therefore, a reasonable platform is vital for preparing readiness to resolve expected and unforeseen issues (GMS, 2024b).

5. Summary

Myanmar’s economic development has fluctuated, with significant reversals recently due to several overlapping causes. From 2011 to 2019, Myanmar had an average 6 percent annual economic growth with significant poverty reduction (World Bank, 2024). During these years, economic corridor development was initiated with partner countries, economic blocs, and associations. Normally, impediments exist to successful economic corridor development. Myanmar’s economy shrank during the COVID-19 pandemic and immediately after political upheavals, and economic activity has remained weak and constrained (World Bank, 2024). Under the circumstances, these challenges are strong and unforeseen.

The geographical location and proximity of neighboring countries are constant. Developing economic corridors must also be considered continuously to sustain national trade and the economy in different contexts.

Currently, developing SEZs in Myanmar has been prioritized as a first step and encouraged by the State Administration Council (SAC) government. Kyaukphyu Deep Sea Port and a new rail link from Yunan to Kyaukphyu are potential future projects serving as a vital supply chain for regional and international economic corridors.

Development partners could be useful for developing economic corridors in ECFs and governors’ forums (GF). Myanmar invites investors and developers in the transport and trade industries, looking to improve cooperation with partners with international collaboration. Independently organizing efficient and site-specific institutions for rerouted economic corridors is also essential.

Implementing bilateral, regional and international agreements such as China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), GMS Cross Border Transport Facilitation Agreement (CBTA), ASEAN framework agreement for multimodal transport (AFAMT) according to respective timelines and scheduling also offer key support to economic corridor development.

Improving the logistics performance index (LPI) is an essential catalyst for conquering economic corridor development-related problems. To enhance service levels in the transport and logistics industries, the National Logistics Master Plan should be used as guidelines, with soft and hard infrastructure project components implemented in a respective time frame.

Developing large transport corridors is increasingly seen as a means of stimulating regional integration and economic growth (Alam, M., et al., 2022). Following strategic guidelines to upgrade national transport corridors to economic, multimodal transport, and logistics corridors, Myanmar must meet criteria for upgrading local economic corridors to achieve seamless connectivity with regional and international economic corridors. Developing economic corridors is an efficient mechanism for hastening national development promptly.

References

- ADB (2011), “Greater Mekong Subregion Cross-Border Transport Facilitation Agreement: Instruments and drafting history”, Mandaluyong City, Philippine

- ADB (2016), “Myanmar Transport Sector Policy Note”, Manila, Philippines

- ADB (2018), “review of configuration of the Greater Mekong Subregion economic corridors”, Manila, Philippines

- ADB (2019), “Myanmar: Progress and Remaining Challenges”, Manila, Philippines

- ADB (2022), “BIMSTEC master plan for transport connectivity”, Manila, Philippines

- ADB (2024), “Asian Economic Integration Report 2024”, Manila, Philippines

- Ahmad, W. (2024), “Introduction to the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)”, Online source retrieved 17.3.2024. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/china-myanmar-economic-corridor/

- Alam, M., et al., (2022), “Wider economic benefits of transport corridors: Evidence from international development organizations”, Journal of Development Economics, Volume 158, 2022

- Aspireias (2023), “China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)”, Online source retrieved 7.4.2024. https://www.aspireias.com/daily-news-analysis-current-affairs/China-Myanmar-Economic-Corridor-CMEC

- Aung, N. H., (2022), “Factors Impacting Foreign Direct Investment: Evidence from Thilawa Special Economic Zone in Myanmar, Research paper for Master of Business Administration, Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, Japan.

- Banomyong, R. (2008), “Logistics Development in the Greater Mekong Subregion: A Study of the North–South Economic Corridor”, Journal of Greater Mekong Subregion Development Studies

- Brunner H. P. (2013), “What is Economic Corridor Development and What Can It Achieve in Asia’s Subregions?”, ADB, Manila, Philippines

- Brunner, H. P. (2013), “What is Economic Corridor Development and What Can It Achieve in Asia’s Subregions?”, ADB

- Cuong M. Nguyen (2016), “6 Challenges to Advancing GMS Economic Corridors”, Online source retrieved 8.4.2024. https://blogs.adb.org/blog/6-challenges-advancing-gms-economic-corridors

- DICA (2024), “Special Economic Zones”, Directorate of Investment and Company Administration (DICA), Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations (MIFER), Myanmar. Online source retrieved 13.4.2024. https://www.dica.gov.mm/en/

- Embassy of India (2022), “Bilateral Economic and Commercial Brief”, Embassy of India, Yangon. Online source retrieved 6.4.2024. https://embassyofindiayangon.gov.in

- ERIA (2009), ‘The Mekong-India Economic Corridor’, ERIA (ed.), Mekong-India Economic Corridor Development-Concept Paper. ERIA Research Project Report 2008-4-2, pp.5-6. Jakarta: ERIA

- GMS (2024a), “Study on strengthening engagement of local governments in the GMS”, interm report for consultations, GMS Secretariat

- GMS (2024b), “Explainer: What is an Economic Corridor?”, Online source retrieved 13.4.2024. https://greatermekong.org/explainer-what-economic-corridor

- Hill, H. and Menon, J. (2020), “Economic Corridors in Southeast Asia: Success Factors, Impacts and Policy”, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

- ISP (2023), “Three New China-Myanmar Cross-Border Trade Routes”, Online source retrieved 7.4.2024. https://ispmyanmar.com/mp-10/

- JICA (2014), “Myanmar National Transport Master Plan”, Naypyitaw, Myanmar

- JICA (2018), “Myanmar National Logistics Master Plan”, Naypyitaw, Myanmar

- Karim, M.A. & Islam, F. (2018), “Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor: Challenges and Prospects”, The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis Vol. 30, No. 2, June 2018, 283-302

- MoCom (2024), “trade situation of Myanmar in 2019-2020 fiscal year to 2023-2024 fiscal year (up to February monthly), Ministry of Commerce, Myanmar.

- MOI (2024), “Myanmar, Thailand decide to enhance economic cooperation”, Online source retrieved 6.4.2024. https://www.moi.gov.mm/moi:eng/news/12811

- MPA (2023), unpublished presentation, Myanma Port Authority, Ministry of Transport and Communications, Myanmar

- Mutangadura, G., (2021), “Institutional-related issues on Economic Corridor’, online training workshop on Strengthening Subregional Connectivity in East and North-East Asia through effective economic corridor management, Online source retrieved 8.4.2024. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/d8files/2021-01/UN-OHRLLS.pdf

- Myers, L, (2020), “The China-Myanmar Economic Corridor and China’s Determination to See It Through”, Online source retrieved 2.04.2024. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/china-myanmar-economic-corridor-and-chinas-determination-see-it-through

- PFS (2024), “Burma – Trade Agreements”, Privacy Shield Framework. Online source retrieved 13.4.2024. https://www.privacyshield.gov/ps/

- Putra, B. A., Darwis, & Burhanuddin. (2019). “ASEAN Political-Security Community: Challenges of establishing regional security in the Southeast Asia.”, Journal of International Studies, 12(1), 33-49

- Rangan Dutta, R. (2018), “North East and the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC)”, ISPSW Strategy Series: Focus on Defense and International Security, Issue No. 529, Jan 2018

- Sawasdee (2023), “Road Linkage Cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar”, Online source retrieved 6.4.2024. https://www.thailand.go.th/issue-focus-detail/001_08_005

- Thaibiz (2020), “Myanmar joins Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) by Ministry of Investment and Foreign Economic Relations (MIFER)”. Online source retrieved 7.4.2024. http://www.thaibizmyanmar.com/th/articles/detail.php?ID=3630

- World Bank (2023), “Connecting to Compete 2023: Trade Logistics in an Uncertain Global Economy”, The Logistics Performance Index and Its Indicators, Washington, DC 20433

- World Bank (2024), “The World Bank in Myanmar”, Online source retrieved 12.4.2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/myanmar/overview