Economic Corridor Development in Thailand

Continental Southeast Asia: Thailand

Professor Ruth Banomyong, Ph.D.

Thammasat University, Thailand

Purim Srisawat. Ph.D.

Ramkhamhaeng University, Thailand

Assistant Professor Wachira Wichitphongsa

Pibulsongkram Rajabhat University, Thailand

1. Introduction

Thailand is rich in natural resources, forests, marine environments, and cultures (Smith, 2020). Diverse businesses and industries such as tourism, agricultural and food, biotechnology, and wellness can potentially be boosted to attract domestic as well as international investments (Jones, 2019). Strategically located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula with border connections to neighboring countries (see figure 1) (Department of Geography, 2021), Thailand has potential to become a central geopolitical gateway to support cross-continental economic ties through land, rail, sea, and air networks (Brown & Green, 2018).

Figure 1 Geographical location of Thailand.

Source: https://www.britannica.com/place/Thailand

These positive factors have motivated the Thai government to explore the concept of economic corridor development (Smith, 2018). Following the economic cooperation development project in six countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (Asian Development Bank, 2020) and the implementation of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by the Government of the People’s Republic of China (Yang, 2019), in 2015 the Thai government has officially begun implementing the concept of revitalizing designated areas into a national Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) in the Eastern region and developing 10 special economic zones (SEZ) at borders (Thai Government Gazette, 2016). This Thai government project aimed to foster local economic and industrial growth and increase national competitiveness (Jones, 2021). Policies, regulations, and institutional frameworks have been set to mobilize people, goods, and capital. Large investments have been planned and executed to enhance physical, financial, digital, and other supporting infrastructures (Lee, 2022). In 2022, with the positive progress of the EEC, national economic corridor development expanded to cover four other regions of Thailand (Wong, 2023).

With a particular focus on regional cooperation initiatives, the Thai government is also participating by investing in regional economic corridor development at different levels, including:

- Bilaterally, emphasizing cooperation and connections to create mutual benefits with individual trading partners and other economic nodes (Clark & Adams, 2021). This includes economic integration with neighboring countries along the border.

- Regionally, by designating special economic corridors to physically and economically integrate selected nations in a focused region, such as GMS cooperation (Nguyen, 2017).

- Internationally, establishing interconnections between Thailand and other countries to create new trading routes, markets, and investment opportunities (Peterson, 2020). This includes BRI participation (Zhang, 2019).

The result of economic corridor development in Thailand is multifold. One targeted outcome is to strengthen and promote local industry. This leads to creating new employment and decentralized economic growth. It also targets improved connectivity and infrastructures between national and cross-border regions to facilitate trade and logistics processes. Increasing economic corridor connectivity may drive regional economic development. Another planned outcome is to create a more business-friendly environment to facilitate investment and business establishments (Miller, 2023)

2. Economic Corridor Development in Thailand

This section provides more details on economic corridor developments currently in Thailand at different levels. They can be described as follows:

2.1. National Economic Corridor Development

The national economic corridor development in Thailand is an evolving concept originating with the Eastern Seaboard Development Program (ESB) in 1982 under the Fifth National Economic and Social Development Plan (1982-1986) (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 1982). Originally, the Thai government strove to transform the national economy from agriculture-based to export-oriented industry (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 1982). Consequently, new industrial clusters in Chachoengsao, Chonburi, and Rayong provinces were designated as potential gateways for international trade and export through the Gulf of Thailand (National Economic and Social Development Board, 1987). Land and basic infrastructure megaprojects and development received investment (Office of Industrial Economics, 1992). For example, two industrial estates, Laem Chabang and Map Ta Phut, emerged along with the development of Map Ta Phut seaport (Thailand Board of Investment, 1995).

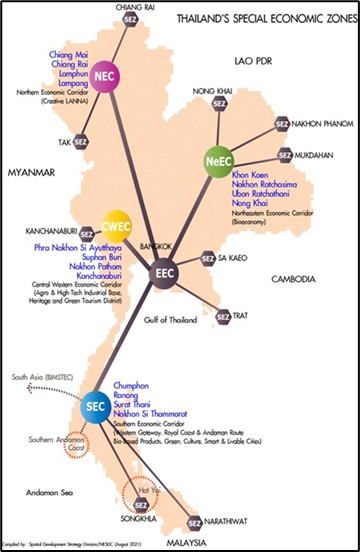

Three decades later, with a slower than anticipated pace in driving gross domestic product (GDP), the first national economic corridor (EEC) was launched as a continuing development phase of ESB (Eastern Economic Corridor Office, 2017). Taking benchmarks from GMS and BRI projects, the first investment budget of US $43 billion went beyond basic infrastructure development to cover advanced logistics networking (high-speed rail, airports, and aerotropolis), personnel, education, research, business, finance, technology, and innovation (Ministry of Transport, 2018). National economic corridor development aimed to decentralize economic and industrial growth, reducing income disparity, raise living standards of local residents, and potentially foster economic connectivity with neighboring countries (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2018). With the positive progress of EEC and an increasing country-wide awareness of sustainable economic development, the concept of developing national economic corridors was integrated into the 20-year national strategy (2018-2037) and the Thirteenth National Economic and Social Development Plan (2023-2027) (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2018). Four additional national economic corridor developments were designated in other regions, including:

- The Northern Economic Corridor (NEC), covering the cluster of Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, Lamphun, and Lampang provinces with the goal of launching an ecosystem to support creative cities and creative industries.

- The Northeastern Economic Corridor (NeEC), covering the cluster of Nakhon Ratchasima, Khon Kaen, Udon Thani, and Nong Khai provinces with the aim of promoting investment in agriculture, bioindustry, and relevant modern industries.

- The Central-Western Economic Corridor (CWEC), covering the cluster of Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Nakhon Pathom, Suphanburi, and Kanchanaburi provinces to support high-value, high-tech industries and economic linkages with Bangkok and EEC;

- The Southern Economic Corridor (SEC), covering the cluster of Chumphon, Ranong, Surat Thani, and Nakhon Si Thammarat provinces to use bioindustry and high-value agricultural processing and enhance the tourism industry along the Andaman coast (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2023).

Currently, Thailand has five economic corridors (see figure 2).

Figure 2 Five national economic corridors in Thailand

Source: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2023

2.2. Bilateral Economic Corridor Development

In 2015, in tandem with EEC development, the Thai government also implemented the SEZ development project (Ministry of Commerce, 2015). This was an effort to further achieve bilateral economic corridors in 10 border cities (Tak, Mukdahan, Sakaeo, Trat, Songkhla, NongKhai, Narathiwat, Chiang Rai, Nakhon Phanom, and Kanchanaburi provinces) with equilibrium and sustainability with other economic gateways of neighboring countries (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2016). Figure 3 illustrates the establishment of these 10 SEZs (with 90 sub-districts of 23 districts in 10 provinces) (National Economic and Social Development Board, 2016).

By exploiting border connections with Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, and Malaysia, investment in cross-border logistics infrastructure to strengthen physical connections and shorten operational lead times at border checkpoints was planned and executed (Thai Customs Department, 2017). For instance, building new roads and upgrading existing ones facilitated smoother transportation of goods and travelers between these border cities and neighboring countries. In addition, customs and immigration facilities were streamlined and modernized to expedite border clearance processes, reducing delays and enhancing efficiency for cross-border trade. Developing integrated SEZ transportation hubs and logistics centers has attracted private investment and fostered economic activity, contributing to overall regional growth and competitiveness. These initiatives align with broader goals of the Ninth Master Plan for balanced and sustainable development across border areas through closer economic ties and mutual benefits with neighboring countries. In addition, institutional frameworks, policies, and regulations to reduce administration processes, alleviate tax burdens, improve service quality, and create investment incentives have been revised and modified (Board of Investment of Thailand, 2017). One-stop service (OSS) points and improved access to foreign workers initiatives were introduced by the Thai government to support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and add new business opportunities (Department of Employment, 2018).

The goals of bilateral economic corridors are to create new economic gateways in border cities linked to neighboring countries. Decentralized economic growth in border cities is expected to enhance quality of life and security of residents on both sides of the border (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2017).

Figure 3 Ten SEZs in Thailand

Source: International Commission of Jurists, 2020

2.3. Regional Economic Corridor Development

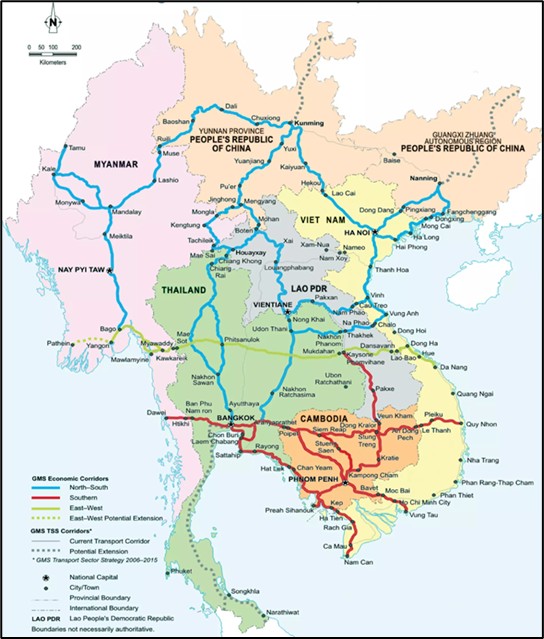

The GMS development project is a vital regional economic corridor contributed by Thailand. GMS aims to accelerate subregional development by economically, socially, and physically linking production, trade, logistics, investment, and personnel between subregional nations (Smith, 2020). The GMS project defines three main regional economic corridors (Johnson & Lee, 2018) (See figure 4). As mentioned, the Thai government has designated and implemented SEZs and national economic corridors to harmonize with the following three main regional GMS economic corridors:

- East-West Economic Corridor (EWEC), connecting Viet Nam-Laos-Thailand-Myanmar (Doe, 2019). Along this corridor, Thailand has designated the Tak border as the main link (and cross-border checkpoint) with Myanmar and Mukdahan border as the main link (and cross-border checkpoint) with Laos (Miller, 2021). The EWEC aims to facilitate regional trade and goods mobilization by reducing transportation burdens (Smith, 2020). Thailand has undertaken several steps to improve road transport infrastructure quality. One main transport project is construction of the R2 with a length of 1,530 kilometers (km), for which Thailand completed its 770 km long portion in 2006 (Johnson & Lee, 2018). Several further intersection areas and trade centers along less developed national routes have been developed and enhanced to create new trade opportunities. In addition, developing the NeEC could also support biological industrial base growth with modern technology, which is one of EWEC’s development guidelines (Doe, 2019).

- North-South Economic Corridor (NSEC), with three subcorridors (Central, Northern, and Southern Coastal) connecting China-Myanmar-Thailand and China-Laos-Viet Nam (Brown, 2017). NSEC also opens access to significant Malaysian and Singaporean markets through major seaports (Adams, 2022). Along this corridor, Thailand has designated the Chiang Rai border as the main link (and cross-border checkpoint) with Myanmar and Laos as well as Songkhla and Narathiwat borders as main links (and cross-border checkpoints) with Malaysia (Clark, 2016). NSEC development processes have been conducted in three phases: 1) developing transport links to form a transport corridor; 2) enhancement from transport corridor to logistics corridor; and 3) enhancement from logistics corridor to economic corridor (Adams, 2022). Large investment projects on transport and cross-border infrastructures have been conducted in Thailand. These include building and improving Route No.3 (R3E) with 830 km in Thailand, R3W with 850 km in Thailand, and two Thai-Laos friendship bridges across the Mekong River (Brown, 2017). Ultimate NSEC goals are to mobilize raw materials and products as well as promoting tourism (Clark, 2016).

- Southern Economic Corridor (SEC), connecting Thailand-Cambodia-Viet Nam. Along the corridor, Thailand has designated Kanchanaburi border as the main link (and cross-border checkpoint) with Myanmar and Sa Kaeo and Trat borders as the main links (and cross-border checkpoints) with Cambodia (Doe, 2019). Two important routes have been built in Thailand to connect economic activities with other economic gateways and promote regional economic cooperation (Smith, 2020). These transport projects include the construction of R1 (with 300 km in Thailand) and R10 (with 380 km in Thailand) (Johnson & Lee, 2018).

Figure 4 GMS and its three main economic corridors

Source: Thailand Board of Investment, 2019

In addition to GMS, Thailand has also contributed to, and participated in, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand – Growth Triangle (IMT-GT) economic cooperation to strengthen Southern economic development. Under IMT-GT, areas of cooperation include creating new investment opportunities, increasing productivity through technology transfer as well as improving infrastructure and transportation connectivity. Thailand has designated eight Southern border provinces to participate in IMT-GT: Songkhla, Pattani, Narathiwat, Yala, Satun, Trang, Phatthalung and Nakhon Si Thammarat. Completed and ongoing investment projects include infrastructure development such as road upgrades and extensions, port expansions to facilitate trade, establishing industrial zones to promote economic growth, developing tourism infrastructure to attract visitors, and investing in education and human resource development to enhance regional skills and capabilities. Additional initiatives are aimed at improving cross-border cooperation and connectivity with neighboring countries to foster regional integration and economic development (Tangtrongjita, 2023).

2.4. International Economic Corridor Development

BRI and its China-Indochina Peninsula economic corridor are important international development initiatives significantly impacting Southeast Asia (SEA) and Thailand (Cheng et al., 2018). The economic corridor extends from China’s Pearl River Delta westward along the Nanchong-Guang’an Expressway and the Nanning-Guangzhou High-speed Railway through Nanning and Pingxiang to other SEA economic nodes, including Hanoi, Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore (Lin, 2019). Due to BRI, large investments on transport, energy supply, and other supporting infrastructure have filled gaps in infrastructure needs (Chen, 2020). One such investment project is building a railway network to facilitate mobilization of people, goods, and capital (Zhao, 2021). Currently, Thailand is undertaking the construction of a railway system under two different phases. The first includes building a 256 km rail route from Bangkok to Nakhon Ratchasima; the second continues the rail route from Nakhon Ratchasima to Nong Khai (Thailand Ministry of Transport, 2022). Once operative, this railway system will be a part of international transport network to connect Thai exports with Asia and Europe (Sompong, 2023). More international visitors for local tourism may also be targeted (Tourism Authority of Thailand, 2023).

Thailand has also participated in technical and economic cooperation among seven countries (Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, Myanmar, Nepal, and Bhutan) in the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi‑Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and participated in promoting the framework agreement on the BIMSTEC Free Trade Area (BIMSTEC Secretariat, 2023). This provides Thailand an opportunity to enhance its international trade and export industry by enabling access to large South Asian markets and consumer populations. It also potentially strengthens South Asian investments in EEC and increases international tourist arrivals (Prachachat, 2023).

3. Challenges to Economic Corridor Development in Thailand

Although extant economic corridors developed in Thailand may drive economic growth and improve living standards for residents, room for improvement remains on economic corridors to fully achieve the targeted impacts. This section contains a discussion on sources of issues and challenges encountered in developing economic corridors in Thailand; the following section recommends mitigation strategies. All challenges and issues may be categorized as follows:

3.1. Infrastructure Challenges

3.1.1. Transport (road/rail/river/coastal/maritime and air)

Despite investments in nationwide road transport infrastructure (intercity motorway development, double track railway system) as well as at main cross-border checkpoints (accelerating the establishment of a one-stop service center), Thailand retains road transport capacities inadequate for coping with high traffic volume (Department of Highways, 2021; Ministry of Transport, 2022). This leads to traffic congestion problems, creating major bottlenecks. Relevant evidence includes heavy congestion on major highways leading to neighboring countries and long waiting times for vehicles at cross-border checkpoints (Royal Thai Customs, 2020; Transport Statistics Sub-Division, 2021). Traffic congestion and transport bottlenecks impede reliability of goods transport and increase transportation costs, negatively impacting local business and national competitiveness (International Trade Centre, 2020). Although relevant local authorities are present at customs clearance/checkpoints, they have separate processes and objectives (Department of Customs, 2022). A lack of system synchronization and cooperation among local authorities incurs unnecessary complex flows of physical goods, administration, and documents, raising operating costs and lead times (National Economic and Social Development Council, 2021).

Demonstrably, longer transport lead time is a major concern for the perishable industry must maintain the time-sensitive products in appropriate temperatures on the route and during cross-border processes (Agricultural Economics Office, 2022).

Building road transport infrastructure is a primary focus in developing economic corridors, but maintenance and repair operations are often neglected. Trivial budget amounts are allotted for transport infrastructure maintenance and repairs (Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning, 2022). This results in safety concerns, transport inefficiencies, and unsustainable economic development (World Bank, 2021). As opposed to road transport infrastructure investment, investment in railway and sea transport infrastructure development in Thailand is always lacking or delayed. As a result, railway and seaport facilities are still underdeveloped and below standard compared to neighboring countries. This potentially hinders international trade and export industry competitiveness as these transport modes are the most inexpensive international options with the least environmental impact (Asian Development Bank, 2020). Also, increasing national railway network capacity may address road transport network inadequacies (Ministry of Transport, 2021).

Air transportation in Thailand faces several challenges, primarily due to economic recovery after the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, infrastructure limitations, and regulatory issues. After the pandemic, nations gradually lifted measures to control international travel. The aviation business has duly recovered with increased travel and cargo transport volumes, but still faces limited growth from inflation and jet fuel prices that have risen in line with world crude oil prices. The impact may not be immediately passed on to service users, because airlines must maintain competitive fare levels due to market mechanisms. In addition, the government sector helps alleviate the cost burden by extending the rental period, service fees, and reducing excise tax on jet fuel. In addition, the airline business has an increased investment burden, from adjusting safety criteria to meet aviation business standards and boosting post-pandemic hygiene levels, adding to operational pressure. This especially impacts businesses lacking liquidity and those in the process of restructuring or rehabilitating from bankruptcy.

In terms of infrastructure, especially in major cities, Thailand’s airports face congestion and capacity constraints. Expansion projects are underway, but progress is slow, hindering the ability to accommodate an increasing number of passengers and flights. Ensuring safety and security standards remains another challenge, with concerns over aviation accidents, terrorism threats, and smuggling activities. Enhancing security measures while maintaining smooth passenger flow is essential. The regulatory environment in Thailand’s aviation sector can be complex and bureaucratic, leading to delays and inefficiencies. Streamlining regulations and improving coordination between different authorities could help address these issues. In addition, Thailand has a shortage of skilled aviation professionals, including pilots, air traffic controllers, and maintenance technicians. Developing training programs and attracting talent to the industry are necessary to address this issue. Finally, the aviation market in Southeast Asia is highly competitive, with many low-cost carriers vying for market share. Thai airlines must innovate and adapt to changing consumer preferences while maintaining cost competitiveness.

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach involving collaboration between government, industry stakeholders, and international partners to ensure sustainable growth and development of Thailand’s air transport sector.

3.1.2. Other Facilities (such as dry ports/warehouses/DC/fulfilment center)

The need for warehousing and other storage facilities is on the rise to support the growth of international trade and e-commerce businesses (Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council, 2023). Having warehouse facilities close to industrial estates, cross-border checkpoints, and other gateways can optimize transportation of goods (full truckloads and goods consolidation), adding supply chain value (cross-docking, transshipment, packaging and labeling, and postponement) (Carolina S. Guina & Pawat Tangtrongjita, 2021). Warehouses may also be intermediate facilities to buffer or safeguard inventories in an attempt to increase transport responsiveness and reduce transport lead time (Division Logistics System Development Strategy, 2023). However, capacities of extant facilities are inadequate for business needs (NESDC, 2022). There is also the issue of insufficient skilled laborers to manage inventory and provide value-added activities at facilities (soft infrastructure) (Bank of Thailand, 2021).

In addition, to align with future investments in different modalities of transport infrastructure (rail, road, and sea), there is an immediate need for dry port infrastructures to support a smooth transition and movement of goods between modalities (intermodal connectivity) and advanced technology integration for transport planning synchronization (Office of Trade Services and Investment Negotiations, 2023). Some investments have been made in infrastructure, but not enough to meet rising demands (NESDC, 2023).

3.2. Institutional Challenges

To further advance economic corridor development, Thailand must address the following additional challenges:

- Coordination and Governance: Effective coordination among multiple government agencies, committees, and stakeholders at national and regional levels is essential for successful economic corridor development. Clear delineation of roles, maintaining policy continuity, and building broad-based institutional ownership should be addressed through strategic coordination and collaboration.

- Infrastructure Development and Regulations: Economic corridors require comprehensive planning and development of modern infrastructure, including transportation networks, logistics facilities, digital connectivity, and industrial estates resolved by public-private partnerships.

- Regulatory Harmonization and Trade Facilitation: Inconsist-ent international regulations, complex administrative procedures, and varying customs processes are obstacles. Regulation for bilateral and subregional agreements, and harmonization of rules and regulations at national and regional levels are imperative for establishing a seamless environment conducive to trade and investment.

- Human Capital and Socioeconomic Development: Upgrading skills, developing entrepreneurs, and promoting inclusive growth are essential for economic corridors. Close collaboration between government, educational institutions, and the private sector is necessary to address human capital development challenges.

- Regional Integration and Market Harmonization: Differences in market economies, development policies, and challenges to integration of regional economic systems exist. Promoting the harmonization of rules and regulations is a key strategy for potential economic corridors in driving regional integration.

3.3. Logistics Service Provider Challenges

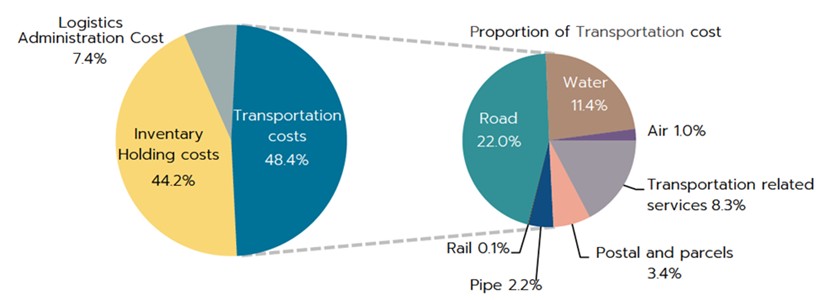

The fluctuation of global fuel prices is an external factor challenging operations and businesses of logistics service providers (LSPs) in Thailand. An immediate consequence of surging fuel prices is an increased operational cost, while the same operational budget and expected profit margins are applied (Thailand’s Logistics Report 2021, 2022). LSPs unable to face these challenges could encounter operational inefficiency, resulting in transport delays and disrupted goods flow (Division Logistics System Development Strategy, 2023). An LSP solution to increase service prices could also deteriorate national competitiveness, needed to sustain international trade businesses and economic growth along the corridors (Action plan for the development of Thailand’s logistics system 20223-2027, 2023).

Another challenge is a lack of skilled manpower in the LSP industry, defined as labour intensive industry (Bank of Thailand, 2021). Based on statistical analysis, shortages of truck drivers, loading operators, and data analysts is a major issue (Cartrack Technology Thailand, 2022).

Figure 5 Logistics cost structure in Thailand 2023

Source: Strategic Logistics Development Division, Thailand 2023

Often, operating LSPs in developing countries such as Thailand involves additional challenges of political and policy instability, especially in areas of customs procedures, road safety, and emission protections (Office of Trade, Services and Investment Negotiations , 2023). Conflicting policies in different countries along a border may also challenge LSP cross-border operations. Along the Thailand border, discrepancies in customs regulations and documentation requirements between Thailand and its neighbouring countries can lead to delays and increased costs for LSPs. Differences in transport regulations, such as weight limits, vehicle specifications, and driver licensing requirements, may pose significant obstacles for LSPs trying to navigate across borders. This can result in disruptions to supply chains, difficulties in meeting delivery deadlines, and increased administrative burdens for companies operating regionally. (Carolina S. Guina, Pawat Tangtrongjita, 2021)

The risk of encountering corruption at border checkpoints is another concern of LSPs that may lead to increased operational cost and transport delay (Division Logistics System Development Strategy, 2023).

3.4. Manufacturing, Trading, and Investing challenges

Tax and non-tax incentives, easy administration processes through one-stop service provisions, and beneficial access to foreign works may be gained when investing and operating businesses in designated economic corridor development areas. Yet investors still face challenges from bureaucracy and regulations (NESDC, 2023):

- Unnecessary, duplicatory paperwork required by different authorities in customs clearance processes (Office of Trade Services and Investment Negotiations, 2023). The amount of paperwork needed varies depending on product type and destination country (Office of Trade Services and Investment Negotiations, 2023). Additional preparation of paperwork is expensive and time consuming (Division Logistics System Development Strategy, 2023).

- Fluctuating border regulations require shippers/ manufacturers/ traders to add extra resources and expenses to stay current and avoid transport delays or incur penalties (Carolina S. Guina & Pawat Tangtrongjita, 2021).

4. How to overcome economic corridor development challenges

Developing economic corridors in Thailand, achieving goals and benefiting regional development requires cooperation from many stakeholders. Economic corridors aim to stimulate economic growth, strengthen connectivity, and promote regional development. However, achieving these objectives requires addressing challenges such as infrastructure development, regulatory frameworks, environmental sustainability, social equality, and stakeholder coordination.

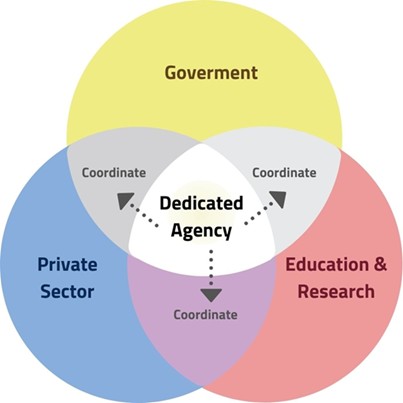

Stakeholders, comprising the government, private sector, and academic and research institutions must push unidirectionally for efficient development of economic corridors. The government must play a key role in developing the regulatory framework, building infrastructure, and necessary policies. It should also coordinate efforts among diverse stakeholders by setting strategic priorities and ensuring that development initiatives are aligned with national development goals. The private sector should participate through financing, implementing, and operating infrastructure projects in economic corridors. Businesses must bring expertise, resources, and practical innovation as key stakeholders in driving economic growth and job creation. They should also invest in infrastructure projects, establish public-private partnerships (PPPs), and leverage networks to promote trade and investment along the corridor. Academic and research institutions may support useful research, technical expertise, and capacity-building initiatives to support economic development paths. They can conduct studies on the economic, social, and environmental impacts of corridor projects, organize training and education programs for stakeholders and facilitate knowledge sharing and innovation.

Figure 6 Stakeholders in economic corridor development.

However, past operations have lacked coordination between agencies and stakeholder groups due to separate budget planning operations and actions to develop infrastructure, personnel, and procedures. This results in duplication of operations and makes economic corridor development inefficient. Therefore, a central agency responsible for coordinating policies and budget plans might be developed to track work performance, gather relevant information, and develop it into a body of knowledge to transmit to stakeholders, support operations, and suggest advice on economic corridor development to domestic and international stakeholders.

Considering priorities for creating economic corridors, infrastructure development is of urgent importance; improving physical infrastructure such as roads, railways, ports, and logistics facilities is essential for strengthening connectivity and facilitating trade and investment along economic corridors. The government should prioritize investment in infrastructure projects that connect key economic centers, reduce transportation costs, and improve market access. Also vital is regulatory reform, improving governance processes, reducing traditional bureaucratic steps, and facilitating business operations. This is a precondition for attracting private sector investment and promoting economic activities in the economic corridor. The government should implement policy reforms that create a business-enabling environment, protect property rights, and ensure regulatory certainty for investors.

However, economic corridor development should focus on environmental and social sustainability to reduce negative impacts and ensure equitable benefits for local communities. Governments should integrate environmental considerations into infrastructure planning and design, promote sustainable land use practices, and investing social infrastructure such as healthcare, education, and housing.

For economic corridor development to continue efficient operations, these policy options should be considered:

- Develop a dedicated agency with a clear governance structure responsible for coordinating economic corridor development, gathering and disseminating information and knowledge, supporting operations, and offering advice for regional development to domestic and international stakeholders as well as representatives from relevant ministries, local government, the private sector, and civil society. This agency should be free from bureaucracy to provide operational independence and flexibility.

- Review the vision, strategy, and development plan for each regional economic corridor to meet current conditions, resolve weaknesses and limitations, and develop strengths and opportunities. Set goals consistent with local conditions for infrastructure, domestic and international connections, and economic characteristics, including regional social and cultural conditions.

- Accelerate development and improvement of the requirements, regulations, and work procedures framework by coordinating with relevant domestic and international agencies to increase transportation efficiency, especially cross-border transport.

- The government should promote PPP, stimulating private sector participation through concession agreements and other innovative financial mechanisms to exploit private sector resources and expertise in infrastructure development.

- Increase human development by investing in education, skills training, and capacity building programs to ensure a ready workforce, including how local communities and businesses will benefit from the economic corridor development initiative.

5. Summary

For over 30 years, Thailand has been developing economic corridors to stimulate the economy and regional integration by adhering to several international cooperation agreements. In doing so, Thailand has learned the following operational lessons:

- Infrastructure improvement through economic corridor development is often related to vital infrastructure such as logistics, industrial areas, and utilities. Thailand has improved infrastructure connections to attract investment and facilitate commerce according to economic corridor strategies.

- Thailand has attempted to build economic diversity through economic corridors by focusing on several sectors: manufacturing, logistics, tourism, and innovation. Focusing on industrial or specific sectors distributes investment for economic corridor development.

- Thailand has issued reform regulations to support development as the appropriate framework and policy are key for attracting investment and facilitating business.

- Regional cooperation development comprises economic corridor improvement, often related to neighboring countries and regional alliances to promote trading, investment, and connections. Thailand has cooperated with China, Japan, and ASEAN nations to develop economic corridors and regional integration.

Overall, economic corridor improvement in Thailand brings many benefits, such as attracting investment, stimulating economic growth, creating employment opportunities, and connecting domestic and international business exchange. However, enduring challenges include infrastructure gaps, policy barriers, economic and social differences, and environmental problems that must be resolved to develop a sustainable economy.

Thailand’s economic corridor improvements benefit those who profit if the government receives more income from international investment and competitive empowerment. Simultaneously, the private sector gaisn advantages from improved infrastructure, market access, and business environment. The local community enjoys employment opportunities, service and infrastructure access, and regional economic growth. However, negative effects include environmental deterioration, foreign investors benefiting from business expansion, new market access, and governmental policies and related supportive factors.

Nevertheless, Thailand should consider economic corridor improvement by using economic development guidelines. The economic corridor is a proven strategy for improving regional economy but requires support through new projects addressing social and economic challenges such as poverty, education, healthcare, and rural development. The focus should also be on innovative creation, digital transformation, and sustainable improvement to ensure future prosperity and flexibility. Improvement must be achieved through a balanced approach to benefit Thailand and its citizens to the highest degree.

References

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. (2023). Action plan for the development of Thailand’s logistics system 20223-2027. (2023). Bangkok.

- Adams, P. (2022). Economic Corridors in Asia: Development and Integration. Asian Development Bank.

- Bank of Thailand. (2021). Thailand Labour Market Restrucing. Bangkok: Bank of Thailand.

- BIMSTEC Secretariat. (2023). Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation. Retrieved 30 December 2023, https://bimstec.org/

- Board of Investment of Thailand. (2017). Policy and incentives for special economic zones. Retrieved 28 December 2023, https://www.boi.go.th/index.php?page=sez_policy

- Brown, J. (2017). Transport Infrastructure and Economic Growth in Southeast Asia. World Bank Publications.

- Brown, L., & Green, M. (2018). Thailand’s role as a geopolitical gateway in Asia. Asian Economic Journal, 14(2), 76-89.

- Carolina S. Guina, Pawat Tangtrongjita. (2021). Thailand: Study on Thailand’s Regional Cooperation and Integration Initiatives and Their Implications on Thailand’s Development. Office of The National Economic and Social Development Council. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

- Cartrack Technology Thailand. (2022, August 10). Problems and crises in the transportation sector from real experiences in 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2024, https://www.thaipr.net: https://www.thaipr.net/business/3223550

- Chen, J. (2020). Infrastructure Investment under the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of Asian Economics, 30(2), 102-115.

- Cheng, L., Wang, Z., & Li, X. (2018). The China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor: A Case Study of the Belt and Road Initiative. Asian Development Review, 35(1), 44-63.

- Clark, H. (2016). Regional Trade and Economic Corridors in Asia. Routledge.

- Clark, M., & Adams, J. (2021). Bilateral economic cooperation: Case studies and strategic insights. International Trade Journal, 35(4), 456-478.

- Department of Customs. (2022). Customs Clearance Processes.

- Department of Employment. (2018). Initiatives for supporting SMEs and new business opportunities. https://www.doe.go.th/prd/assets/upload/files

- Division Logistics System Development Strategy. (2023, May-August). International Logistics Performance Index 2023. Newsletter, pp. 10-12.

- Doe, J. (2019). Subregional Development Projects and Economic Integration. Oxford University Press.

- Eastern Economic Corridor Office. (2017). Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) Development Plan. Bangkok: Eastern Economic Corridor Office.

- EECO. (n.d.). Government initiative. https://www.eeco.or.th/th/government-initiative

- ITD. (n.d.). IMT-GT overview. Retived 20 January 2024 https://www.itd.or.th/itd-research/issues-01/

- Johnson, R., & Lee, S. (2018). The Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation. Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, A. (2019). Economic potential of Thailand’s diverse industries. International Business Review, 22(4), 101-115.

- Jones, R. (2021). Competitiveness in the Thai economy: A policy analysis. Journal of Economic Policy, 48(2), 123-145.

- Lee, S. (2022). Infrastructure development in Southeast Asia: Trends and challenges. Infrastructure Journal, 29(3), 301-320.

- Lin, Y. (2019). Economic Corridors and Regional Development: The Case of the China-Indochina Peninsula Corridor. International Journal of Transport Economics, 46(3), 301-320.

- Miller, P. (2023). Business environment reforms in developing economies. Business Review Quarterly, 37(1), 67-89.

- Miller, T. (2021). Border Trade and Economic Corridors. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ministry of Commerce. (2015). The 9th Master Plan for economic development. Retrieved 12 January 2024, http://www.moc.go.th/9th_master_plan

- Ministry of Transport. (2018). Infrastructure Development Plan for Economic Corridors. Bangkok: Ministry of Transport.

- Ministry of Transport. (2021). Railway Network Development. Bangkok

- Ministry of Transport. (2022). Road Transport Infrastructure Investments. Bangkok

- Money Buffalo. (n.d.). Which provinces are the new economic corridor and what do people in the area get. Retrieved https://www.moneybuffalo.in.th/economy/which-provinces-are-the-new-economic-corridor-what-do-people-in-the-area-get

- National Economic and Social Development Board. (1987). Industrial Cluster Development in Thailand. Bangkok: National Economic and Social Development Board.

- National Economic and Social Development Board. (2016). Establishment of special economic zones in Thailand. Retrieved 18 November 2023, http://www.nesdb.go.th/special_economic_zones

- National Economic and Social Development Council. (2021). System Synchronization Among Authorities.

- NESDC. (2022). Thailand’s Logistics Report 2021. Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC).

- NESDC. (2023). System Synchronization Among Authorities. Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

- Nguyen, H. (2017). Regional economic integration: The Greater Mekong Subregion. Southeast Asian Studies Journal, 23(2), 213-235.

- Office of Industrial Economics. (1992). Industrial Estates and Development in Thailand. Bangkok: Office of Industrial Economics.

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. (1982). The 5th National Economic and Social Development Plan (1982-1986). Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. (2018). The 20-Year National Strategy (2018-2037). Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council. (2023). Action Plan for the Development of Thailand’s Logistics System 2023-2027. Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council.

- Office of Trade, Services and Investment Negotiations . (2023). Overview of logistics services of Thailand. Bangkok: Department of Trade Negotiations.

- Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning. (2022). Budget for Transport Infrastructure Maintenance.

- Peterson, L. (2020). Global trade routes and economic corridors. World Trade Review, 19(1), 89-108.

- Prachachat. (2023). EEC Investment Opportunities and Tourism Potential.

- Royal Thai Customs. (2020). Cross-Border Checkpoint Efficiency.

- Smith, A. (2018). Economic corridors: A new paradigm for growth. Economic Development Quarterly, 32(1), 45-60.

- Smith, A. (2020). Logistics and Trade Facilitation in the GMS. International Journal of Economic Studies.

- Smith, J. (2020). Natural resources and environmental wealth of Thailand. Environmental Studies Journal, 15(3), 45-60.

- Sompong, T. (2023). The Impact of the New Railway System on Thai Exports. Thai Journal of Economics, 55(4), 215-230.

- Tangtrongjita, P. (2023). Review and Aseessment of The Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle Economic Corridor. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

- Thai Customs Department. (2017). Cross-border logistics and infrastructure development. Retrieved from https://www.customs.go.th/2017_infrastructure

- Thai Government Gazette. (2016). Announcement of the Eastern Economic Corridor Development Plan. Bangkok: Government of Thailand.

- Thailand Board of Investment. (1995). Industrial Estates and Development. Bangkok: Thailand Board of Investment.

- Thailand’s Logistics Report 2021. (2022). Bangkok: Office of the National Economic and Social Development Council (NESDC).

- ThaiPublica. (2012, November 13). 30 years of the Eastern Seaboard development: Sustainable development? ThaiPublica. https://thaipublica.org/2012/11/30-years-eastern-seaboard-development/

- Tourism Authority of Thailand. (2023). Strategies to Boost International Tourism.

- Transport Statistics Sub-Division. (2021). Highway Congestion Data.

- Wong, T. (2023). Expansion of economic corridors in Thailand. Thai Economic Journal, 54(1), 22-35.

- World Bank. (2021). Transport Inefficiencies and Economic Development.

- Yang, M. (2019). China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Impact and implementation. Journal of International Affairs, 72(3), 289-309.

- Zhang, Q. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative: A Chinese strategy for global economic integration. Asian Economic Policy Review, 14(2), 142-159.

- Zhao, X. (2021). Railway Networks and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Belt and Road Initiative. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 134, 347-361.